Semiconductor sovereignty could be the answer to chip shortages, but it'll take time

Taking silicon in-house is one route to salvation

Get all the latest news, reviews, deals and buying guides on gorgeous tech, home and active products from the T3 experts

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

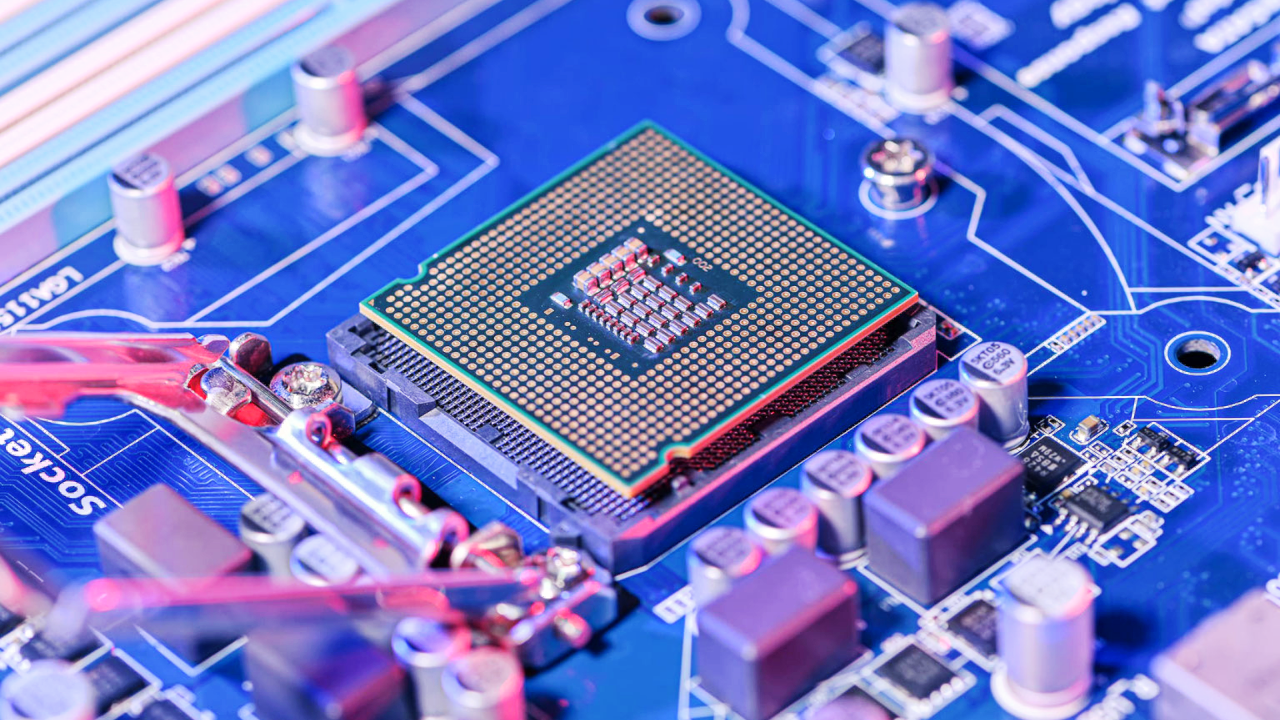

The tech industry is at a critical point. Chipset shortages are affecting products across the globe – automobiles, the best washing machine units, and many of the best phones – all of which rely on silicon chips, also known as semiconductors. Shortages of semiconductors, the chips that do everything from helping toasters work to making your best laptop the pride of your workspace, have been a persistent problem during the pandemic.

While this shortage of chips has hindered many industries over the past year, smartphone sales have remained relatively stable to date. Unfortunately, things could be about to change with supply constraints likely to worsen before they get better, even predicted to affect smartphone sales by the millions. Numerous reports predict the crisis continuing far into 2022 and there are still no signs of it letting up.

- Google Chrome just got a pair of awesome upgrades

- Facebook's Apple Watch competitor leaks, and it's got a camera notch

- 5 viral TikTok hacks to help you fall asleep faster

The chip shortage will start “hitting the smartphone industry hard,” – that's according to the latest report from Counterpoint Research. The study notes that the situation is presently worsening with the likes of Apple warning of problems ahead as we move through Q3 2021. If you're trying to ferret out the good news amongst the doom and gloom of Counterpoint's Research, then a simple look at global smartphone makers' actions supports this dreary outlook. Some smartphone makers are now reporting that they're only receiving 70 percent of their sales requests, creating multiple problems and skewering the forecast for the second half of 2021.

They're not alone, either. Buying a PS5 games console has been out of the question for a while now. Even T3's 5 quick PS5 tips article for beating the bots is up against it, as readers ferociously type to bag a console before the 'Out of Stock' page flashes onto the screen. And with smartphone makers now feeling the pinch too, the semiconductor shortage has got a grip on us all.

Demand

How does the world get salvation from the semiconductor crisis? Gary James, a member of ICIS (Independent Commodity Intelligence Services), says it's a question that's hard to answer right now: "There's no sort of golden bullet to this. I think we're just going to have to slowly globally move out of it." ICIS monitors a range of markets and provides its customers with a view of how these respective markets are performing against each other. From petrochemicals, PVC, plasticizers, lots of markets' businesses have ground to a halt this year, as companies search for a quick solution. The problem is: there doesn't seem to be one.

When it comes to silicon chips, the causes of the shortages are as varied as they are difficult to deal with. "Global lockdown, chip production facilities shutting down, even the trade war and laws between China and the US – all of those have contributed to the silicon shortage," says Gary. These issues have imposed restrictions on semiconductor manufacturing and have been aggravated by the pandemic. It's a situation that's been developing for a very long time, not just months.

The warning signs were there early. As the pandemic arrived on the global stage, erratic demand led to the stockpiling of electronic components and tech firms bulk ordering silicon, which left other smaller companies struggling to acquire the supplies they needed. Japan's Renesas suffered a huge fire last year as well. The fire-damaged chip plant "supplies around 30 percent of the global market for the microcontroller units in cars," and it's compounded the crisis. On paper, it's scarcely believable that such a menagerie of catastrophes came together to produce a silicon drought, but it's all too real for the industries impacted by it on a day-to-day basis.

Get all the latest news, reviews, deals and buying guides on gorgeous tech, home and active products from the T3 experts

Tricky Terrain

The ongoing global semiconductor shortage is one of the reasons why phone companies and other tech firms alike are thinking twice about where they source their chips from. Though the tech industry was inevitably heading to a place where companies produced their own chipsets in-house, the pandemic has hurried the process along. Innovation has, it seems, been limited by chipmaker timelines.

The current landscape isn't straightforward either: several companies, like Intel, known as Integrated Device Manufacturers (IDMs), already handle the design and manufacturing of their chipsets and have done so for decades. Other 'Fabless' companies design their own semiconductors but don't manufacture them. And then there are companies like Samsung and TSMC, which run fabs where chips can be ordered from wholesale. "Chip production is not linear and most businesses will delegate some aspect of the semiconductor manufacturing process," says Gary James. With different companies at various points on the silicon manufacturing roadmap, it's often hard to align.

Semiconductor Sovereignty

The pushes and pulls on semiconductor production are also reflective of many countries' ongoing geopolitical quests to secure supply chain sovereignty. But for phone manufacturers who are feeling the strain of chronic shortages, where firms like Apple may have to slash iPhone 13 production because chip suppliers can't meet the demand for the new smartphone, it's become an existential problem. The response from some companies is to head down the path of self-sufficiency and forge a path of survival.

China's leading smartphone maker, Oppo, is one such firm rumored to be heading down the path to develop its own high-end chips. T3 reached out to Oppo for comment on speculation surrounding the move, and it said: “Oppo maintains a strong relationship with all industrial chain partners, including Qualcomm and MediaTek. Regarding the rumors, we do not comment, and there is no other information to share”. Despite the lack of information, a company as big as Oppo surely can't rely on foreign semiconductor suppliers, such as Qualcomm and MediaTek, especially if it's limiting its business through lack of stock.

Oppo's lips are firmly sealed, for the time being, but you probably wouldn't want to bet against Oppo raising the stakes by taking its silicon production in-house. After all, the move would arrive shortly after Google, with the release of the Pixel 6 and Pixel 6 Pro, its first phones with a custom system-on-a-chip (SoC) called Tensor.

In-house production

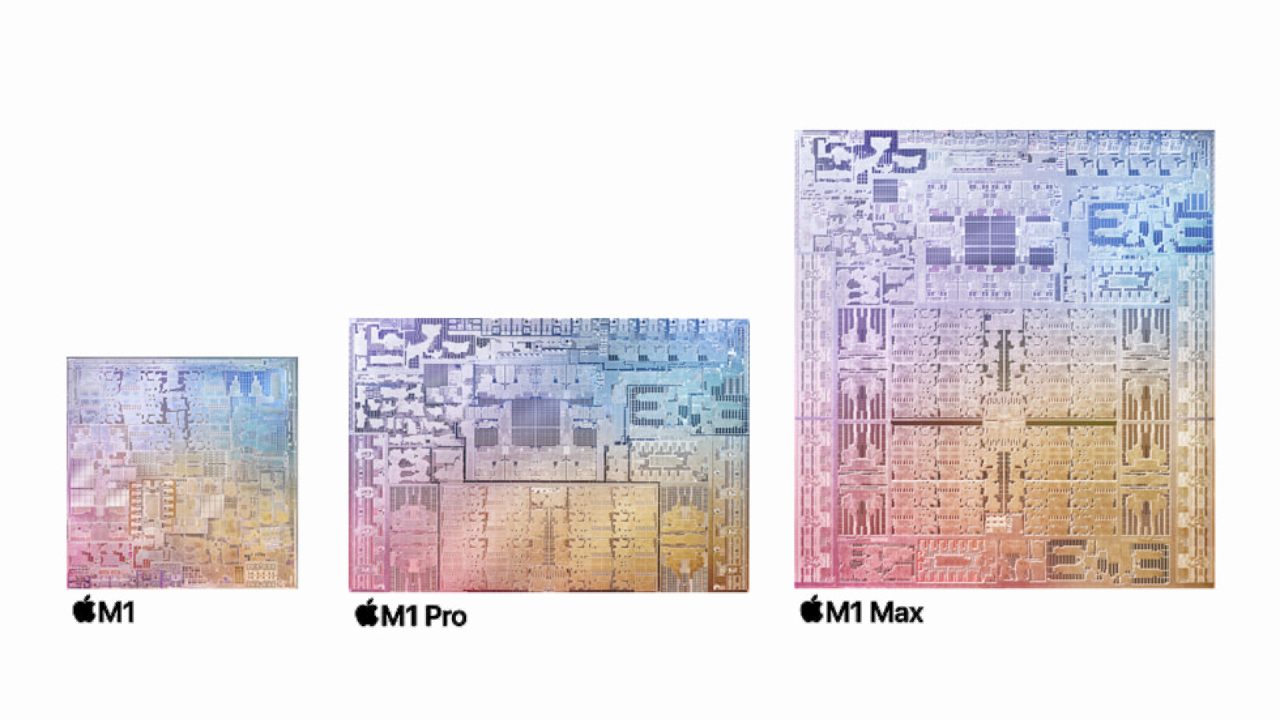

Other smartphone titans like Apple and Samsung are also designing their own smartphone chips, as did Huawei before US sanctions crippled the company and the subsequent sell-off leveled its business. Apple is a company that has already realized the potential of in-house chip design with its M-series of SoCs. "You only need to take one look at the new MacBook Pro 2021", says Marcus Wilson who is a Product Manager for Channels, AI, and Innovation at Vodafone. "The benchmarks for the M1 Max against the exact same hardware with an Intel chip. Apple is able to unlock much more potential from that chip, especially when it's manufacturing it in-house."

It's an interesting observation from someone on the network provider side, and a sentiment that's felt throughout the wider company. What makes Oppo’s journey particularly intriguing, of course, is that it plans to collaborate with the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. Ltd. (TSMC) to leverage the the company's advanced 3nm process technology to produce superior chips with increased transistor density, increased speed and reduced power consumption. Apple and Intel are two such 3nm customers, so Oppo would be joining a prestigious roster of customers.

A phrase that we haven't mentioned too much here is 5G. The scramble to produce in-house chips will hopefully help produce a wave of accessible 5G smartphones. The entry price point for the best 5G phones is still fairly hefty, but it's something that would allow users to capitalize on Vodafone's future plans for more 5G rollout. Like silicon production, Marcus explains that there are different stages of 5G at the moment, where Vodafone is using "the first stage across many areas of the country before trying to roll out the second stage, which enables faster speeds, lower latency," which is something he hopes a new crop of in-house silicon fuelled phones can thrive on.

To be clear: the semiconductor supply chain has too many areas to be exclusive to one country and is likely to remain global. From chip design to wafer processing, it's a complex and layered process that extends to testing through to materials supply, and then onwards again to assembly and packaging. An eco-system this large has space for sovereignty and self-sufficiency, but there'll always be a need for partnership. It's where this line falls and how quickly companies can align that'll help solve the semiconductor shortage.

Luke is a former news writer at T3 who covered all things tech at T3. Disc golf enthusiast, keen jogger, and fond of all things outdoors (when not indoors messing around with gadgets), Luke wrote about a wide-array of subjects for T3.com, including Android Auto, WhatsApp, Sky, Virgin Media, Amazon Kindle, Windows 11, Chromebooks, iPhones and much more, too.