Is Gore-Tex ePE the future of sustainable waterproof technology? We asked a fabric expert

Does the evolution of Gore-Tex’s ePE membrane mean we can buy guilt-free gear again?

The list of milestones displayed on the wall of W. L. Gore & Associates’ European headquarters in Feldkirchen-Westerham, is both impressive and interesting. Since Bob Gore accidentally invented it in 1969, Gore-Tex (a miracle membrane used in outerwear that can keep water and wind out while still allowing body vapor to escape) has been integral to producing high-performing protective garments worn by explorers venturing to the very extremities of Planet Earth and beyond. Gore-Tex features in gear worn at the planet’s poles and atop highest its peaks, and it’s found in space suits worn by astronauts on missions in space, and in the valves used during heart surgery for that matter.

Achim Ewers zum Rode - Gore's Global Brand and Consumer Strategy Leader, walks and talks us through the wall of fame

Used in everything from the best lightweight waterproof jackets and cold-weather gloves to high-end hiking boots and walking shoes, Gore-Tex has been synonymous with adventure for decades.

In some respects – although it remains an expensive ingredient used primarily in premium products – this magical membrane has helped democratize the outdoors by making it possible for reasonably average people (like me) to explore further than we’d ever be capable of venturing without it (at least not without exposing ourselves to the very real danger of freezing to death or dying of exposure).

I’ve stood on the very rooftop of a couple of continents completely cocooned in Gore-Tex gear, quite literally from my fingertips to my toes, and without it, I may well have left some of those digits up there.

A new Gore-Tex jacket being waterboarded in the rain room

But the reason I’m here, being shown around the Gore-Tex mothership and meeting some of the people responsible for future-proofing the company, is because the production and proliferation of such pricey high-performance gear has also come at an environmental cost.

Recently, however – after years of research, testing and development – Gore has succeeded in reinventing their membrane, and now they really want to tell the outdoor world all about ePE, which they say is more environmentally friendly and will ultimately replace the old ePTFE-based technology.

So, along with various other outdoorsy journalists, I’ve been invited to Feldkirchen-Westerham, close to the Germany–Austria border, to hear, see and feel how this new membrane works and to actually test some items of apparel made with the mark-II material in the nearby mountains.

Get all the latest news, reviews, deals and buying guides on gorgeous tech, home and active products from the T3 experts

Which is exciting. But I also really want to know how legitimate the claims being made about ePE are in terms of it being gentler on the natural environment. Are we being greenwashed by Gore, or can we go out and buy guilt-free gear?

Is Gore-Tex bad for the environment?

In order to make the windproof, waterproof and breathable garments (WWBs) we all demand, Gore’s all-important membrane is invariably wrapped in a laminate with synthetic materials (essentially plastic, a product of the fossil fuel industry that will never, ever biodegrade).

Plus, the composition and production of the membrane itself has – until now – involved the use of Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE), and then the clothing is treated in a durable water repellent (DWR) finish that has, until recently, featured damaging ‘forever chemicals’ like perfluorocarbons (PFCs).

For decades the performance of Gore-Tex gear has been based on the properties of an ePTFE membrane, which is covered in extremely tiny holes – so small they won’t let water molecules or wind through but will let vapour out, which is how it manages to be both windproof, waterproof and breathable (at least in the right conditions, but more of that later).

PTFE is an inert fluoropolymer that doesn’t break down or degrade, and according to Gore (and an independent textile expert I later consulted), is not a PFC of environmental concern – although some chemists take a different view, reasoning that the jury is still out. It also increases the durability – and therefore useful lifespan – of a garment, which lowers its environmental footprint (so long as people are not tempted and lured into repeatedly buying new gear before their old kit has really died).

The spray test

Nevertheless, questions remain about what happens to the PTFEs during disposal (even if you try and do the right thing, textile sorters currently separate out the outdoor garments which might have a DWR on them and do not send these into the textile-to-textile recycling system for fear of contamination – instead they get sent overseas and might be burned or dumped).

Also, the process of creating all those tiny holes in the microporous membrane that allows the magic to happen is done with the use of fluorines, which are being banned because they’re awful for the environment. Gore stood to lose its Bluesign badging when the PFC ban came in unless the company discontinued its use of PFCs in their manufacturing process.

Of course, the outdoor apparel industry is not the only sector guilty of using such chemicals and materials – PTFE is used in everything from plumber’s tape to medical equipment – and Gore is far from the only company involved (every brand producing microporous waterproof and breathable gear is in the same boat).

But with an audience and consumer base comprised of people who place great importance on the preservation of nature, leading outdoor names are especially vulnerable to accusations of non-sustainability or – worse – environmental damage. Gore-Tex is a component product used by high-end brands such as Patagonia that desperately want (need) to preserve their image as an environmentally conscious company.

So there are lots of pressures at play, but there’s also a sense of earnestness around the Gore-Tex team tasked with making their product more planet-friendly, and this is very clearly evident in the people who proudly present their new and evolving product to us.

How does ePE differ to the 'old' Gore-Tex stuff?

Old and new side by side. There is little to no perceptible difference between garments with the ePE (let) and PTFE (right) membrane

With ePE, which remains a microporous membrane that works in exactly the same way as its predecessor, those all-important little holes are created by heating and stretching the material (there’s a bit more to it than that, but you get the drift, and it doesn’t involve the use of any nasty fluorines). Elsewhere in the outdoor industry, a similar switch is being made, except most other companies are using the wording Olefin membranes instead of ePE.

This is touted as the major change (and it is a big deal for Gore, who has devoted a lot of time to developing it), but arguably it’s the stripping out of PFCs from DWR treatments that’s far more consequential since these ‘forever chemicals’ come off during use, they’re bioaccumulative and do not break down in the environment, and they’re cancer-inducing.

Does ePE work?

Leading brands, including Adidas, Arc’teryx, Patagonia, and Salomon, have been producing products featuring Gore’s ePE membrane over the last 18 months. It’s still early days, and information from independent in-field testing is hard to come by, but Gore says gear made with their new membrane and laminate (which is all PFC-free, including the DWR treatment) is just as durably waterproof, reliably breathable and totally windproof as their old tried and trusted apparel.

To demonstrate this, we get to see examples of the material being put through a rigorous testing process at the Feldkirchen product development laboratory, where jackets made by brands that use Gore-Tex are subjected to a sustained all-direction soaking in the rain room (think water jets blast mannequins wearing the apparel for hours), and the fabric gets repeatedly scrunched up by a machine called the Crumpleflexer, which sounds like something out of Willy Wonka's factory that I don't want to get caught up in. I even get a chance to put a sample jacket on, don some protective goggles and step into a wind tunnel where I can assess the garments’ windproof performance in a simulated storm.

The Crumpleflexer tortures the material to simulate repeated use

Leaving the lab, we cross the border into Austria and spend an entire day climbing via ferrata routes on the flanks of Harauer Spitze in the Chiemgaur Alpen, clad in prototype Gore-Tex jackets made with the new ePE tech (and constructed from recycled materials).

Unfortunately (for the purposes of the exercise), it doesn’t rain, but I do get to experience firsthand the look, feel and finish of the gear. I also get an insight into the breathability of the fabric as I work up a proper sweat while climbing the crag and then test its windproof qualities when I’m greeted by a stiff breeze at the summit.

Here, high in the Austrian mountains, where the nearest seaside is Venice, 500km away, the air humidity is low and so a microporous membrane like Gore-Tex works brilliantly in terms of breathability. (This isn’t always the case, but that’s another topic.)

What impact might ePE have on the outdoor industry?

The presentations, demonstrations and testing experiences are all very compelling, but while I’m an enthusiastic and experienced outdoorsy type, and I know what technology works best in particular terrain types, I’m far from an environmental scientist or – more to the point – a textile expert. So once home, I spoke to someone who is, to get their informed take on ePE and what it means for the outdoor industry.

Charles Ross is a university lecturer at the Royal College of Art and works closely with Leeds University. He is the subject lead in Performance Sportswear Design, and many of his former students now work with brands like Mountain Equipment, Montane, Rab, The North Face, Patagonia and Arc’teryx – one is actually on the Gore-Tex team. Inside and outside of work, he’s a self-confessed textile geek. And so, of course, he has been taking a keen interest in the development of ePE, and the claims that it’s more environmentally friendly.

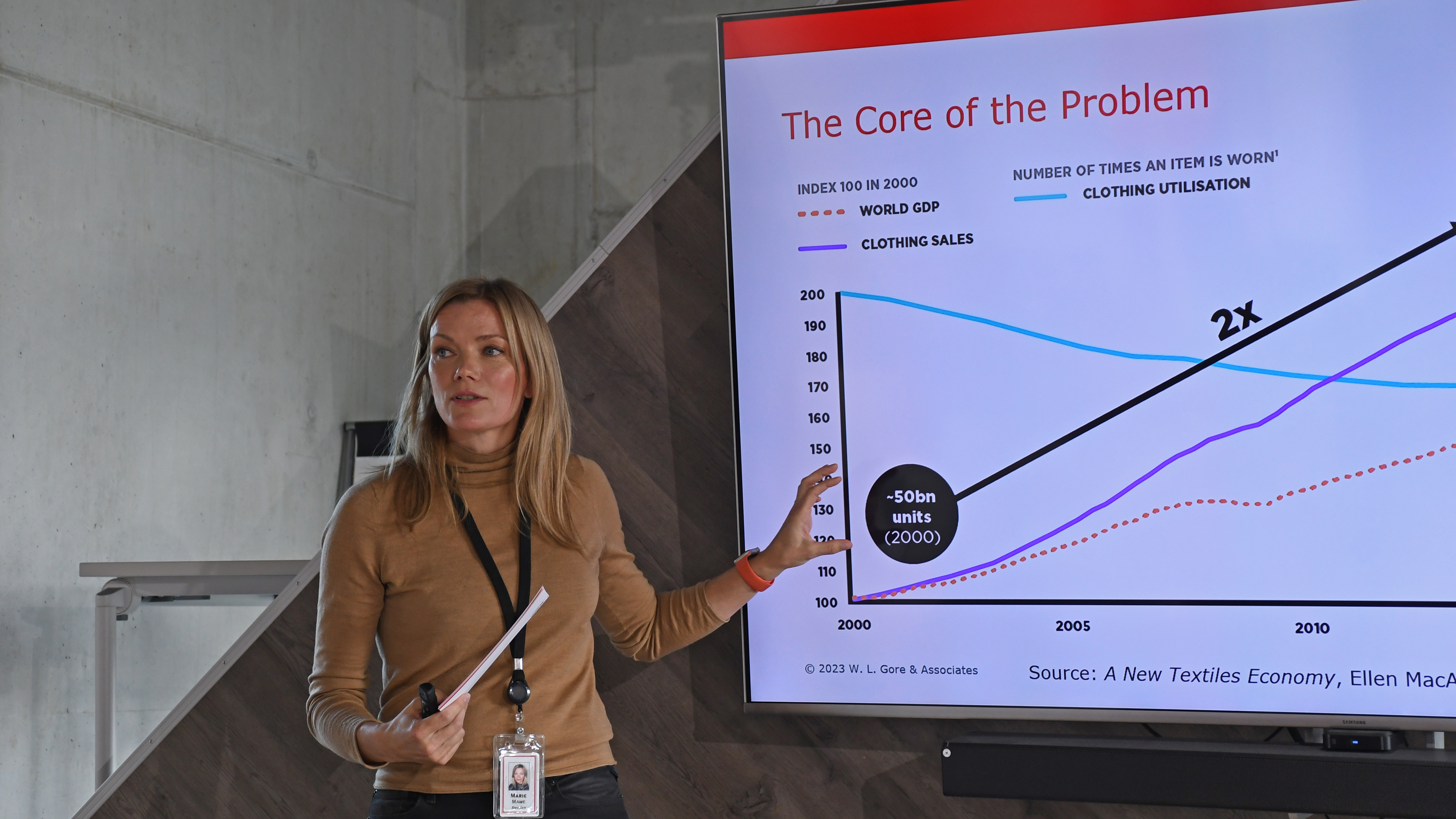

Marie Mawe, Sustainability Stakeholder Engagement Director, Gore Fabrics Division, present the unarguable case for durable gear being better for the planet

“There’s no real change in the membrane in sustainability terms,” Charles tells me. “Because, although the previous version was made with PTFE, the material itself was inert and did not leach out chemicals. However, the construction method is definitely better, as PFCs are not used.”

In terms of performance, Charles says: “The new membrane is very comparable to the Gore-Tex of old, but not the highest permeability product – think more classic Gore-Tex rather than Gore-Tex Pro. I do expect the new (poly)Olefin membrane to have improved permeability in years to come, however. Now they have a stable membrane, Gore will concentrate on getting better breathability figures.”

However, he cautions that better breathability stats are often arrived at via the production of a thinner fabric, which won’t last as long. “There’s always a compromise,” Charles chuckles. A truly magic material that is both genuinely waterproof and highly breathable doesn’t exist.

But the removal of ‘forever chemicals’ from durable waterproof repellency treatments is unquestionably a good thing for the environment, although one issue Charles highlights with the new PFC-free DWRs is that they’re more prone to staining. “I am now seeing garments being junked within a year because they look grubby!” he laments.

Should you buy ePE apparel?

“I define sustainability as the gear you use for the longest – the lowest impact kit is the stuff you already own,” Charles concludes. “So if you have an ePTFE Gore-Tex jacket with a PFC DWR, keep using it; anything you replace it with will be additional footprints.”

However, saluting Gore’s contribution to the development of outdoor gear, Charles tells me: “They have advanced the market and the consumer’s expectations brilliantly. Without Gore, the whole user experience would not be as good.”

He likens the evolution of Gore-Tex (and windproof, waterproof and breathable apparel in general) to a journey and sees the development of ePE as a positive turn of direction along the way. So, if you are investing in new gear because your old kit has genuinely died, then it makes sense to go with equipment made without the use of environmentally damaging chemicals – but don’t go binning it and buying more just because it looks a bit stained.

And treat it with respect; technical clothing like Gore-Tex can only be used a certain amount of times before the laminate fails – save it for when you really need it, and you’ll get years of exciting use out of it, which is better for your pocket and the planet.

And so the journey continues. With slightly lighter footsteps.

Author of Caving, Canyoning, Coasteering…, a recently released book about all kinds of outdoor adventures around Britain, Pat Kinsella has been writing about outdoor pursuits and adventure sports for two decades. In pursuit of stories he’s canoed Canada’s Yukon River, climbed Mont Blanc and Kilimanjaro, skied and mountain biked across the Norwegian Alps, run ultras across the roof of Mauritius and through the hills of the Himalayas, and set short-lived speed records for trail-running Australia’s highest peaks and New Zealand’s nine Great Walks. A former editor of several Australian magazines he’s a longtime contributor to publications including Sidetracked, Outdoor, National Geographic Traveller, Trail Running, The Great Outdoors, Outdoor Fitness and Adventure Travel, and a regular writer for Lonely Planet (for whom he compiled, edited and co-wrote the Atlas of Adventure, a guide to outdoor pursuits around the globe). He’s authored guides to exploring the coastline and countryside of Devon and Dorset, and recently wrote a book about pub walks. Follow Pat's adventures on Strava and instagram.