What's breathability: Understanding breathability ratings of fabrics

Manufacturers throw around all kinds of breathability numbers, figures and facts, but what do they all mean?

When you invest your hard-earned cash in expensive outdoor gear, such as the best waterproof jackets, the best hiking boots or even the best walking trousers, one of the first things you will most likely look at is how waterproof the product claims to be. However, a good waterproof rating means nothing if the fabric isn't breathable. What's breathability, and what's a good breathability rating? Read on to find out.

The Hydrostatic Head (HH) rating (more on HH here: How to stay dry outdoors) of the materials used won’t tell you everything you need to know about how waterproof a garment genuinely is (it’s just as important to look at how well the seams have been sealed and how good the zips and other design elements are), but a crucial factor to weigh up alongside waterproofing credentials is how breathable the boots or jacket is.

There is no point keeping all the exterior moisture out, only to end up soaked from condensation and sweat that has built up on the inside of your clothes because you’re wearing something essentially made of non-permeable plastic. This is where breathability comes into play.

What's breathability: Understanding breathability

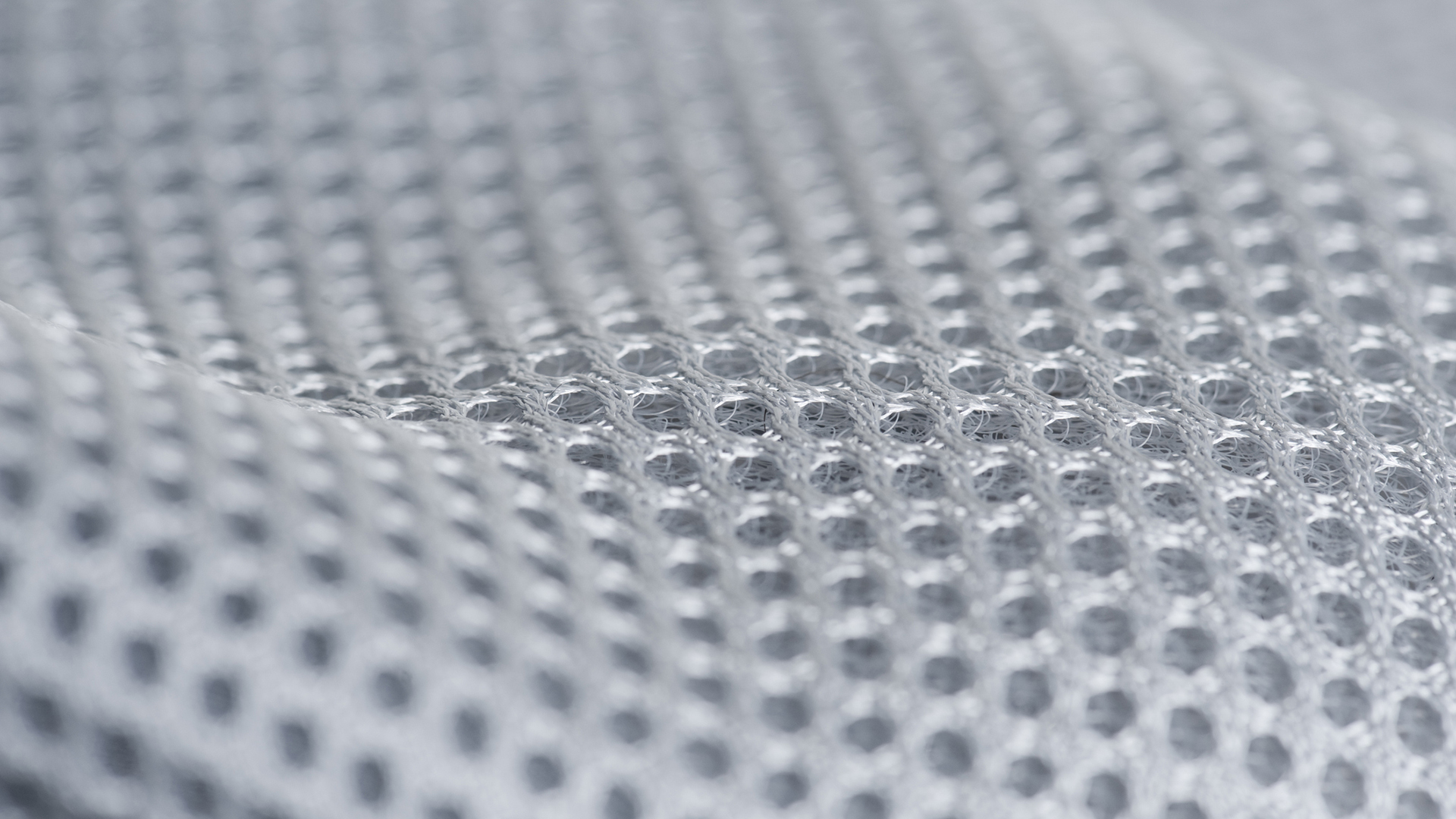

Breathability is the term used to describe how effectively the fabrics used in wearable, waterproof products allow the moisture vapour created by warm-blooded bodies to pass from the inside to the outside.

Various things play into determining how breathable a material is, including its thickness and composition, but in technical apparel and footwear, the most important factor is the performance of the technical membrane – for example, Gore-Tex – incorporated in the design of the product.

This is an extremely important factor when you’re weighing up waterproof jackets for high-intensity outdoor activities, including hiking, biking, running, climbing and cross-country skiing. When it comes to mountaineering, the degree of breathability in something like a jacket can be absolutely crucial because if the moisture can’t escape, it will cool your body down dangerously fast and can lead to life-threatening conditions such as hypothermia.

But if you think waterproof rating methods are complicated and opaque (and they are), then just wait until you try and get your head around how the breathability of outdoor products is worked out and presented. Luckily, we’re here to help untangle it a bit.

Get all the latest news, reviews, deals and buying guides on gorgeous tech, home and active products from the T3 experts

Breathability is presented in several different ways. Two of the most commonly seen are the Moisture Vapour Transmission Rate (MVTR) scale and the Resistance to Evaporative Heat Transfer (RET) scale.

Moisture Vapour Transmission Rate

Let’s take MVRT first. This rating is calculated during laboratory tests, in which the quantity of water vapour that passes through the fabric under scrutiny during a 24-hour period is recorded.

On a product, this is usually shown, for example, as ’15,000 g/m²/24h’ as in the Finisterre Stormbird jacket – which means 15,000 grams of water passed through one square metre of the material over the course of a full day during test conditions. So, with an MVRT rating, the bigger the figure, the more breathable the product is.

However, these are just a series of numbers and letters to most people, so here is what that means in reality:

- 5,000-10,000 g/m2/day – fine for low-intensity activities and day-to-day outdoor use, but not breathable enough for more aerobic activities like trail running, bike riding or fast packing.

- 10,000-15,000 g/m2/day – Good for more vigorous activities such as hiking, ski touring, and mountaineering.

- 20,000+ g/m2/day – The most breathable garments for more intense aerobic activities like trail running or ski-mountaineering.

Resistance to Evaporative Heat Transfer

The RET rating, however, is calculated completely differently. Also conducted in laboratory conditions, this test records clothing evaporative resistance by using sweating thermal manikins (external link). In this case, the less resistance, the lower the number and the more breathable the garment is.

If the RET rating is 0–6, the garment will have superb breathability and be suitable for use during highly energetic activities; a RET rating of 6–13 is still very good, and will work for most outdoor pursuits; 13–20 is fine for gentle walking; anything with a RET rating of 20+ will barely breath at all.

Other considerations

But, just as a HH rating doesn’t tell the whole story about how waterproof a garment is, so an RET or MVRT rating only give you an indication of how truly breathable a piece of clothing is. You also need to take into consideration things like design and vents.

And one last tip: garments that are capable of breathing will operate at their best level to prevent the build up of condensation if they’re quite close fitting, because moisture will build up within air pockets if the inner and outer layers are not touching.

Author of Caving, Canyoning, Coasteering…, a recently released book about all kinds of outdoor adventures around Britain, Pat Kinsella has been writing about outdoor pursuits and adventure sports for two decades. In pursuit of stories he’s canoed Canada’s Yukon River, climbed Mont Blanc and Kilimanjaro, skied and mountain biked across the Norwegian Alps, run ultras across the roof of Mauritius and through the hills of the Himalayas, and set short-lived speed records for trail-running Australia’s highest peaks and New Zealand’s nine Great Walks. A former editor of several Australian magazines he’s a longtime contributor to publications including Sidetracked, Outdoor, National Geographic Traveller, Trail Running, The Great Outdoors, Outdoor Fitness and Adventure Travel, and a regular writer for Lonely Planet (for whom he compiled, edited and co-wrote the Atlas of Adventure, a guide to outdoor pursuits around the globe). He’s authored guides to exploring the coastline and countryside of Devon and Dorset, and recently wrote a book about pub walks. Follow Pat's adventures on Strava and instagram.