I always thought Patagonia’s Yvon Chouinard did more for the planet than The North Face’s Doug Tompkins – I was wrong

The North Face founder’s wild, untold legacy of saving Patagonia

Get all the latest news, reviews, deals and buying guides on gorgeous tech, home and active products from the T3 experts

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

I’ve always believed that Patagonia founder Yvon Chouinard was the gold standard for environmental action in the outdoor industry. He famously turned his billion-dollar company into an activist platform, funnelling profits into climate campaigns and, most famously, “gave away” the company in 2022 so that every penny it made would go towards protecting the planet.

The North Face’s founder, Doug Tompkins? I thought his story ended in the early ’70s, when he sold the company and moved on to Esprit, a label we’d now call fast fashion, founded by his ex-wife Susie Tompkins. In my mind, he’d never made the kind of environmental impact Chouinard had. I was wrong.

It turns out that Doug Tompkins not only shared Chouinard’s passion for wild places; he acted on it in an entirely different, but equally bold way. Together with his wife, Kris Tompkins – who also happens to be Patagonia's first CEO – he poured his fortune into buying millions of acres of pristine wilderness in Chile and Argentina.

I know this because I watched Wild Life (available on Disney+ in the UK), a documentary made after the death of Doug by the team behind the wildly successful Free Solo, featuring Kris and retelling the incredible story in the most fascinating way possible.

A lifelong pull towards Patagonia

Doug’s fascination with Patagonia began in the 1960s, when he first ventured into the southern reaches of Chile and Argentina on climbing and skiing trips.

He was captivated by the raw drama of the place. Here was a wilderness on a scale he’d never seen before, and crucially, one that was still largely untouched by roads, industry, and mass tourism.

For him, Patagonia was a vision of what the world could still protect, unlike so many places in North America that had already been carved up by development. Even during his time building Esprit into a global brand, that image of Patagonia lingered, growing more urgent as he witnessed the environmental cost of consumerism and resource extraction.

Get all the latest news, reviews, deals and buying guides on gorgeous tech, home and active products from the T3 experts

By the late 1980s, he’d had enough of business. In 1989, he left Esprit, moved to the remote Chacabuco Valley in southern Chile, and set out on a mission to buy vast tracts of ecologically significant land, restore them, and ultimately hand them over to the state as national parks. This was conservation at the largest possible scale, and Patagonia was the stage for it.

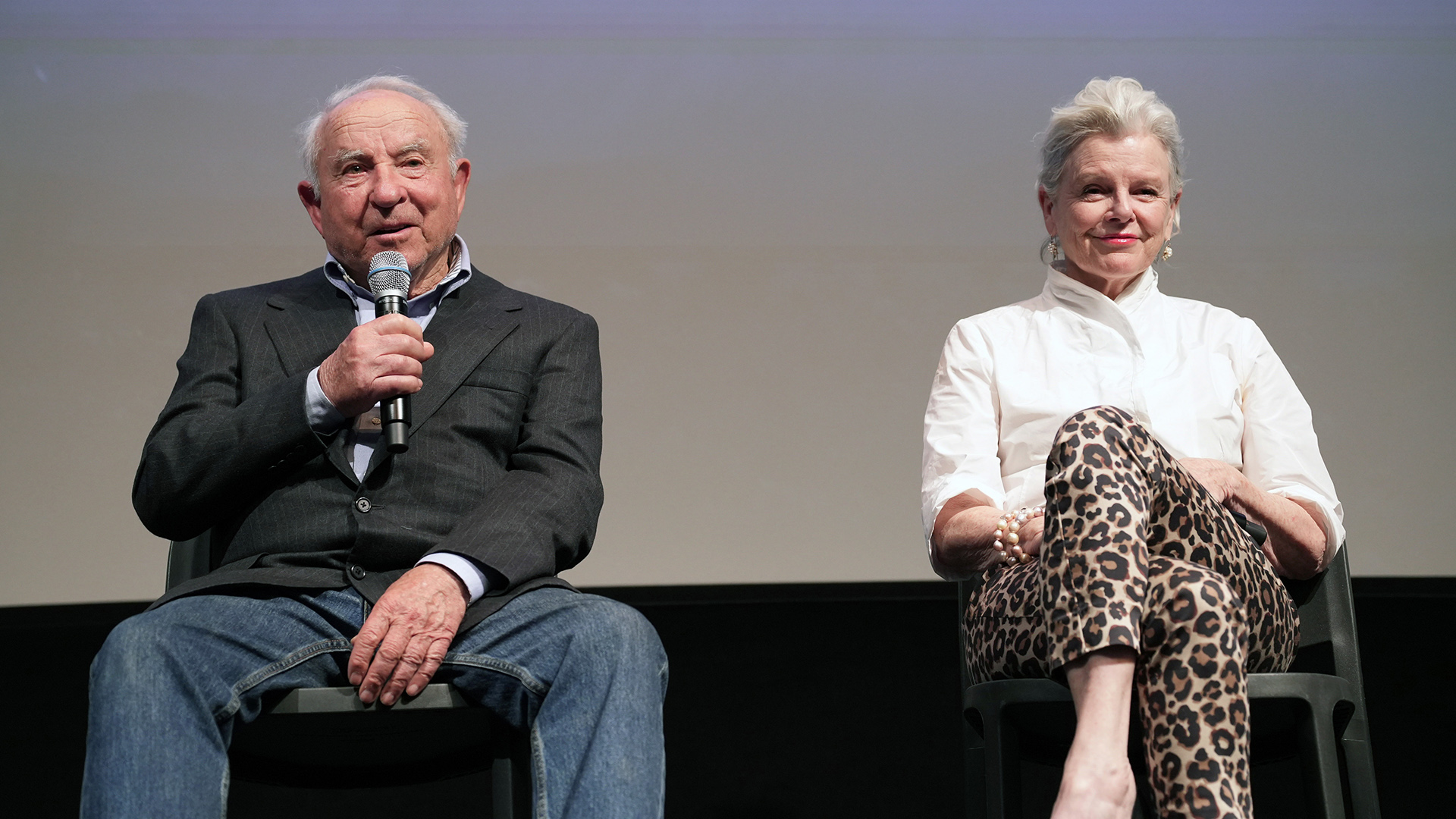

Yvon Chouinard and Kristine Tompkins on stage during the New York Premiere of "Wild Life" at the Museum of Modern Art on April 11, 2023

Protecting Patagonia: Two different playbooks

Founded in the early 1990s, Tompkins Conservation buys threatened wildlands in Chile and Argentina, restores their ecosystems, and donates them to the state as national parks. To date, it has helped create or expand 15 national parks, safeguarding vast ecosystems from grasslands to glaciers.

The work is more than drawing borders on a map. Native wildlife, including the huemul deer, Darwin’s rhea, and Andean condor, has been reintroduced, entire habitats rehabilitated, and local communities brought into the fold through conservation jobs and sustainable tourism. This is conservation as direct action: securing the land before industry can touch it, then protecting it for the public good.

Conversely, Chouinard’s approach has always been about using his company as a megaphone and a funding engine for environmental causes. Patagonia commits 1% of sales (not just profits) to grassroots environmental groups, contributing over $140 million so far to campaigns that range from defending public lands to restoring rivers.

The brand has fought loudly against destructive projects like oil drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge and the downsizing of Bears Ears National Monument. At the same time, it has transformed its own supply chain, using recycled fabrics, regenerative organic cotton, and other innovations to reduce environmental impact.

Both paths are powerful: Tompkins Conservation’s is rooted in locking up land for nature; Patagonia’s in funding, influencing policy, and reshaping business norms. Two complementary strategies, born from the same love for wild places.

Friends to the end

It might seem that Doug Tompkins and Yvon Chouinard were rivals, but that couldn't be further from the truth. In fact, the two were close friends and lifelong climbing and adventuring partners.

For example, Doug was the one who first took Yvon to Patagonia, inspiring the name of the latter's company. They climbed together, travelled together, and shared the same ethos. Yvon took Kris to Patagonia on a work retreat where she first met Doug. Not to mention, Yvon was with Doug in 2015 when he died unexpectedly after a kayaking accident in Chile.

While Chouinard’s legacy is tied to business, turning Patagonia into a perpetual funding machine for activism, Tompkins’ was rooted in direct action: buying the land itself and ensuring it could never be exploited. I found it incredible to learn how these completely different approaches essentially result in the same thing: making the planet a better place to live for all of us.

Mount Fitz Roy at Los Glaciares National Park, near El Calafate, Argentina

Wild ambitions

After Doug’s death, Kris carried on the mission and eventually finished it. Working with governments and local communities, she successfully turned the land they’d acquired into a network of national parks.

It was a project that was started before eco-activism was a thing in an environment that was sceptical about foreigners coming in and buying up huge swathes of land (understandably so, if I may add).

The couple fought hard, often against hostile governments, suspicious locals, and the logistical nightmare of managing vast, remote landscapes. But they succeeded.

Today, thanks to the Tompkins Conservation project, over 14 million acres across South America have been permanently protected. That’s more land than some countries even have.

Kris' work is still ongoing, protecting ecosystems ranging from grasslands to glaciers, and providing sanctuary for species like pumas, condors, and guanacos. It’s a remarkable achievement, made even more so by the grief she must have endured while doing it.

A film worth watching

All of this is laid out in Wild Life, the documentary by Jimmy Chin and Chai Vasarhelyi. It’s an environmental film, a love story, an adventure film, and an inspiring reminder that billionaires can, in fact, use their wealth for something other than vanity projects.

If you’ve ever admired Patagonia’s activism, watching Wild Life will make you rethink what “doing good” looks like and appreciate that there’s more than one way to protect the planet. Watch Wild Life, and prepare to have your assumptions challenged.

Matt Kollat is a journalist and content creator for T3.com and T3 Magazine, where he works as Active Editor. His areas of expertise include wearables, drones, action cameras, fitness equipment, nutrition and outdoor gear. He joined T3 in 2019.

His work has also appeared on TechRadar and Fit&Well, and he has collaborated with creators such as Garage Gym Reviews. Matt has served as a judge for multiple industry awards, including the ESSNAwards. When he isn’t running, cycling or testing new kit, he’s usually roaming the countryside with a camera or experimenting with new audio and video gear.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.