Meet the robots going places humans cannot reach

When you need to access some of the world's most unexplored places, these ARE the droids you are looking for

Get all the latest news, reviews, deals and buying guides on gorgeous tech, home and active products from the T3 experts

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

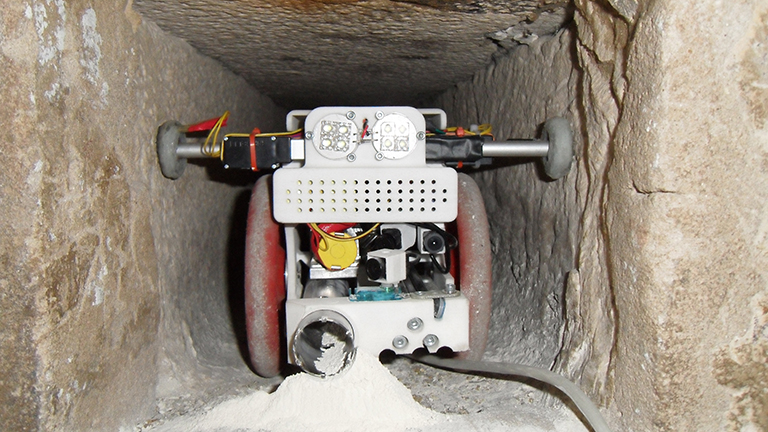

For thousands of years, one tiny part of the world had remained shielded from human eyes, until a few years ago. A small machine was able to fit through a previously inaccessibly space, marking the start of a new era of robotics.

The small chamber in the Great Pyramid of Giza had been hidden from our view, but now robotic exploration is allowing us to virtually venture places we never considered going.

Whether it is an archaeological expedition, monitoring inside the human body or rescuing people after natural disasters, there are some places impossible for humans to go. In these cases, robots can fill an invaluable role – exploring these dangerous places without putting humans’ lives in harm’s way.

Exploration robots are often small and need tiny mechanisms, actuators, sensors and electronics. On top of this, they all need to be able to operate at a considerable distance from human intervention for long periods of time.

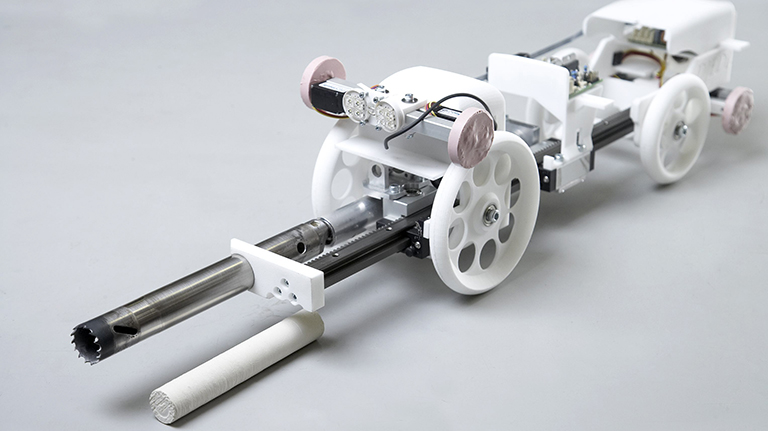

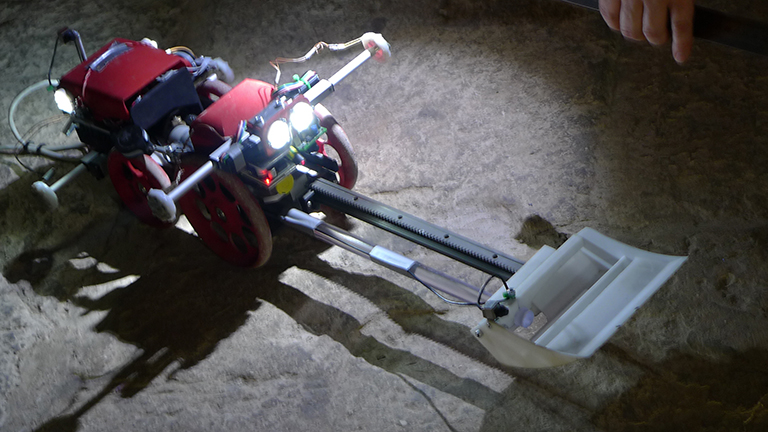

One of the first robots able to get over these difficult hurdles was the Djedi robot. Built by University of Leeds researchers alongside Scoutek founder Shaun Whitehead, Djedi was sent on a mission to explore the pyramids in 2012.

“Djedi was built specially for the shafts in the Great Pyramid, and unfortunately the problems and politics in Egypt meant that we could not return,” Whitehead told T3.

“In the meantime, we continue to develop technology to explore difficult spaces,” he said. One example of these spaces is the glacial lakes at the foot of Everest, which the team have been exploring using tiny boat-shaped robots.

Get all the latest news, reviews, deals and buying guides on gorgeous tech, home and active products from the T3 experts

Known as BathyBot, the tiny catamaran helps glaciologists study climate change by exploring the depth of glacial ponds that can only be reached by foot. Last year, BathyBot had its first mission on the Khumbu Glacier in the Everest region of Nepal.

“It had to be designed to withstand low temperatures, but also we needed it to be capable of being hiked to the location by scientists,” said Whitehead.

“We also had to remember that the scientists would be operating it using thick, warm gloves, so we had to make it as simple to assemble, from as few pieces as possible, and every one of those pieces had to have an easy way to lock it into position.”

By measuring the depth of the lakes, BathyBot helped scientists characterise the volume and compare this to the surface area, as seen by satellites.

“We were able to survey parts of the glacier that would have been very dangerous and difficult to access otherwise,” Owen King, from the University of Leeds and researcher on the project, told T3.

“We used it to measure the depth and therefore volume of lakes filling with meltwater at the surface of Khumbu Glacier. By using BathyBot we were able to do this accurately and over a huge area of the glacier.”

BathyBot will swim again. “The robot is being modified for deployment in other scenarios, such as the Amazon river, to look at sediment and produce accurate models of features on the river,” said Whitehead. This will provide more challenges for the team. “The river is much more ‘choppy’ and faster flowing, so speed, power and stability of the BathyBot are more important than endurance.”

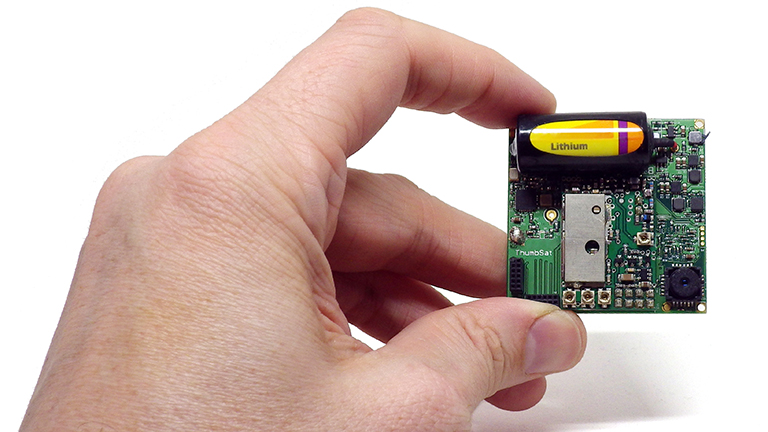

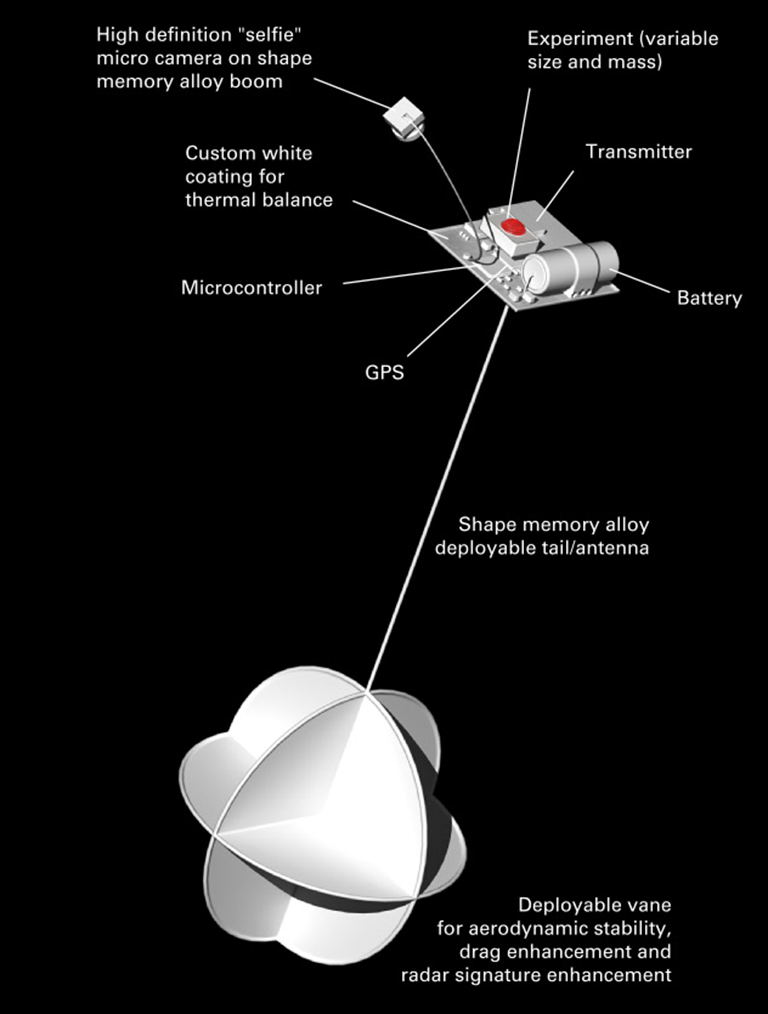

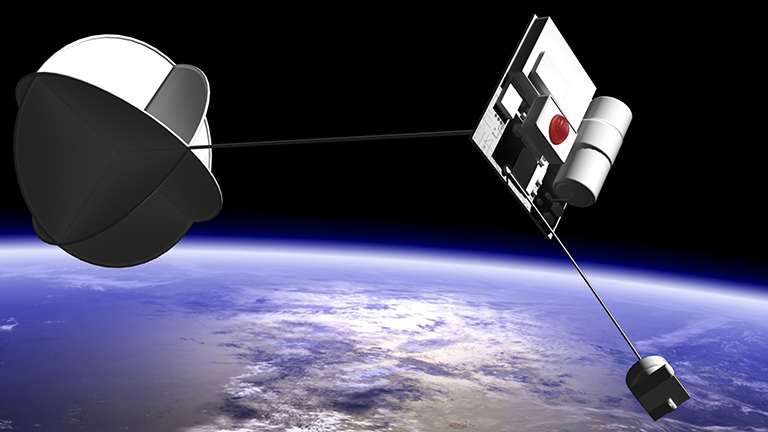

But Whitehead and the team are not confining their exploration to this planet. Next month, they hope to see the first mission of their fleet of tiny satellites, ThumbSats. “Environments don't get any more difficult than space,” said Whitehead.

The aim of the tiny satellites is to make space exploration cheaper. Because each satellite is so light, only 25g, more can fit on a rocket. The cost of sending an experiment on a ThumbSat will start at around $20,000 (£15,640), the group says.

The first fleet of ThumbSats is expected to launch next month, going into orbit around Earth for a short amount of time. They will blast off on an Electron rocket built by US space company Rocket Lab. “We are just waiting for our ride,” said Whitehead.