Tech augmentation: building human 2.0

Could we ever match Halo's Master Chief or Deus Ex's Adam Jensen when it comes to technological upgrades?

There are two ways to upgrade a human - tinker with biology or augment with technology. So when the time comes to upgrade to human 2.0, should we become Bioshock-style splicers or Halo-esque spartans?

This week we look at the science behind a technological upgrade.

Building an exoskeleton

SPARTANS are physically, genetically and technologically augmented to become elite Covenant-busting human weapons with upgraded biology and powered assault armour. And their superhuman mods aren't as far off as they first seem.

Most exoskeleton technology is geared at the medical market, including the impressive ReWalk, a powered hip and knee exoskeleton licensed for the rehabilitation of people with spinal cord injuries in the USA. But there are an increasing number of suits being designed to upgrade healthy human abilities.

EksoBionics specialise in wearable robotics, and their exoskeletons are designed to supercharge human construction workers. Their powered arm, the EksoZeroG bears the load of heavy hand tools, and their new ExoVest takes the effort out of overhead arm movement, giving a lift-assist of up to 6.8kg to each arm.

And, if it's a body suit you're after, Sarcos are building Guardian XO, a full-on exoskeleton that looks like it came straight out of Destiny 2.

Upgrading your hardware

Spartans are more than just their suits. They also undergo a gruelling series of physical augments before they hit the battlefield, and some of them are pretty close to mods that are already available, or in development.

Get all the latest news, reviews, deals and buying guides on gorgeous tech, home and active products from the T3 experts

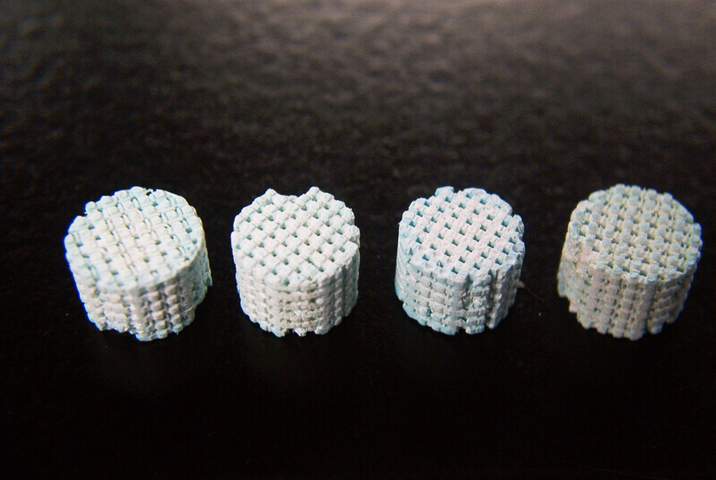

The fictional "carbide ceramic ossification" mod is a strengthening bone graft based on real-world tech - ceramics and bioactive glass. These implants are strong but brittle and, like their Halo counterparts, they can be laced with growth-promoting chemicals, like strontium, which encourage the formation of new bone.

They can also be engineered to leach a steady stream of growth enhancers to encourage the surrounding tissue to mesh with, and eventually overrun, the implant.

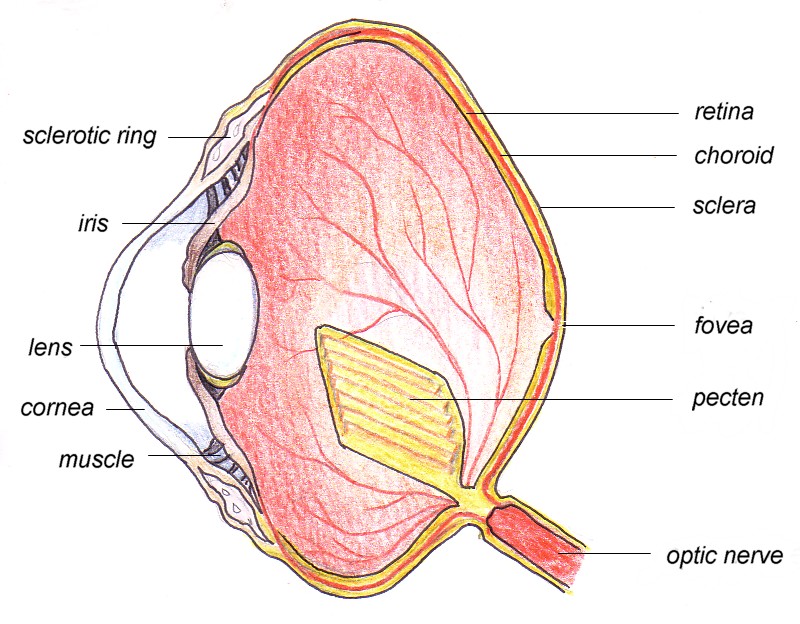

Spartan hopefuls also receive eye augments known in-game as "occipital capillary reversal". This corrects a design-flaw in the human eye that puts our light-sensing cells behind a wall of blood vessels, obscuring our view.

Birds use a similar trick to accentuate their eyesight, keeping their blood supply in a comb-like structure called the pecten. It sits away from the light-sensitive retina, contributing to their phenomenal visual acuity.

This kind of biological rewiring is beyond the scope of current tech, but Second Sight are developing retinal implants that can deliver signals straight to the nerve cells in the back of the eye, using a camera to feed images to the brain. At the moment, the picture it can produce is very low-res, but tech just keeps getting smaller, and the resolution likely to improve over time.

Rewiring your nervous system

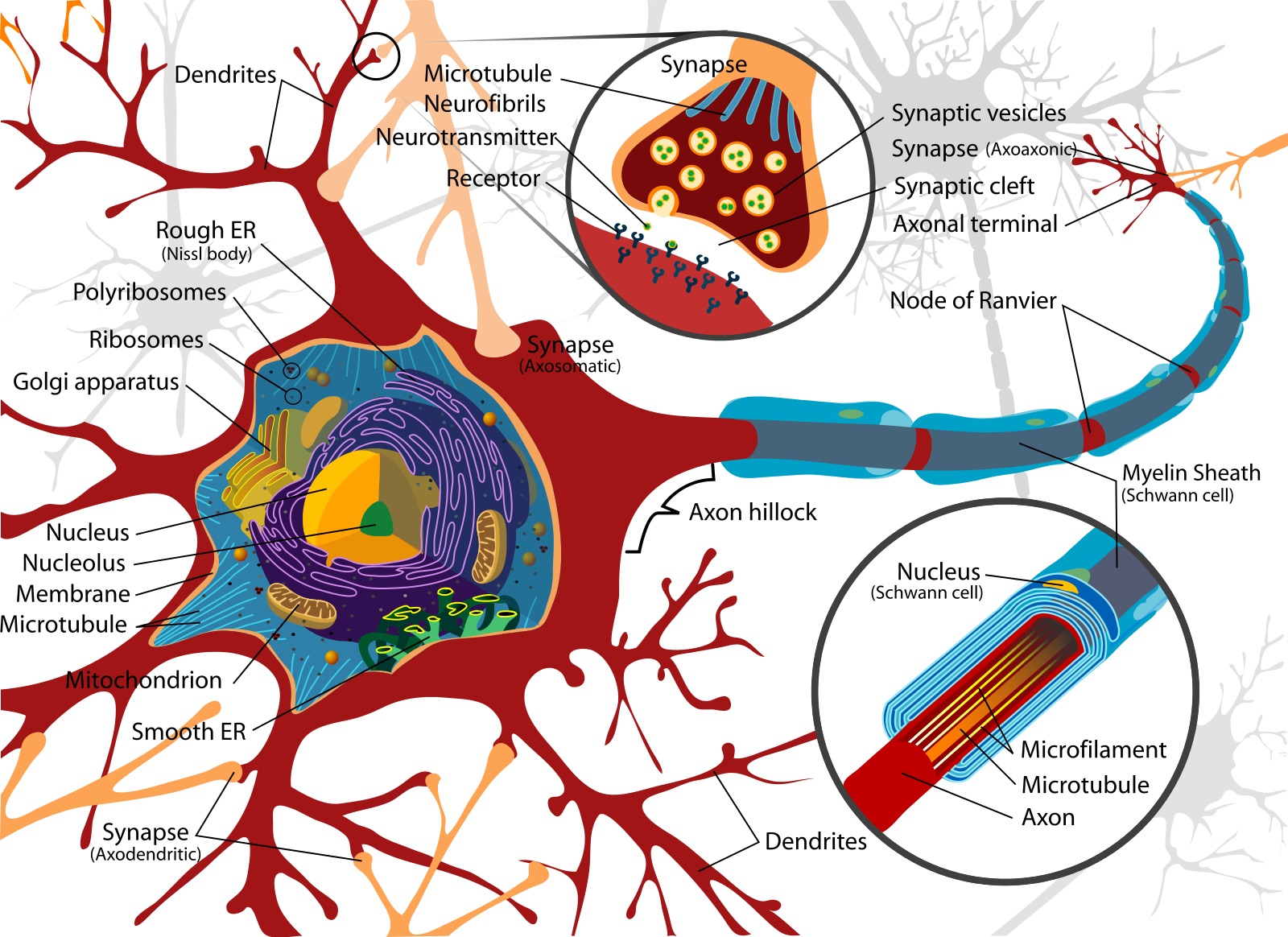

Spartans have one more trick up their tech-enhanced sleeves: artificially insulated nerves that conduct 300 times faster than their natural counterparts. Given that the fastest nerves in the human body can already transmit impulses at 250 miles per hour, that's quite the upgrade.

Fast-conducting nerve fibres are naturally insulated by layers of fatty sheathing called myelin, which works a bit like the insulation on a wire. And scientists are already working on ways to regrow this shielding when nerves get damaged. This is done using hollow fibre-filled tubes with channels that encourage nerve growth (one is made from a combination pig veins and spider silk).

But a Halo-style speed boost probably calls for something more powerful.

Artificial nerves made from conductive polymers are being developed to simulate human cells. And man-made touch sensors made from charged silicone and carbon nanotubules are also undergoing research.

This kind of augment is still in development, but once nervous-system upgrades are perfected, we could enter an era of Deus Ex-like mods.

Implanting augments

Conducting polymers form the basis of the Deus Ex PEDOT cluster array, an implant attached to artificial neurones and embedded in the brain. It's designed to tweak nerve activity, delivering subtle upgrades to existing human abilities, from social enhancement to aim stabilisation. And, it allows the user to interface with advanced implantable tech.

In the real world, pacemakers, hip replacements and cochlear implants are already available, and science-fiction-worthy mods are on the way.

You can now get an RFID chip embedded into your hand, allowing you to unlock doors or open railway barriers at the merest of waves. And, just last month, it was announced that scientists had managed to miniaturise wireless antennas, bringing the idea of wi-fi enabled, internet-of-things-style brain implants a little bit closer to reality.

Sadly, we're still a way away from Jensen's implanted body armour, which combines microfibre, carbon nanotubes and a shear-thickening fluid to absorb impacts (in theory this should work like hitting custard with a hammer).

But, perhaps most intriguingly of all, the US Department of Defence at DARPA are working "using targeted stimulation of the peripheral nervous system to exploit the body’s natural ability to quickly and effectively heal itself”.

They've called their system ElextRX, and their aim is to command the nervous system to tweak the way it senses and responds to damage. Sounds very similar to the Deus Ex Sentinel RX health system to us.

The risks of robotics

Tech upgrades are certainly coming, but there are still some hurdles to overcome before we'll see Spartans and Augs roaming the streets.

Several of Halo's Spartan candidates die during the transformation process, and in the Deus Ex universe, glial scars that block the interface between tech and biology. This leads to a condition called Darrow Deficiency Syndrome, only treatable with a lifelong course of fantasy drug Neuropozyne.

In reality, our own immune systems could put up similar barriers. White blood cells aren't fond of foreign bodies, and they have a habit of reacting to metals, polymers and other implant components causing inflammation, scarring and rejection.

The ultimate aim, of course, is to construct implants to be biocompatible, meshing seamlessly with human tissue. But then we get to the thorny issue of upgrades.

How many times have you changed your phone in the past five years?

There’s only so much surgery a body can take, and you can bet a brand new mod would be released just after you'd had yours fitted. Luckily, scientists are developing dissolving electronics, which could help out-dated augments melt away when the next big thing comes along.

And then there's the ever-present threat of hacking. Augments in Deus Ex were hijacked and controlled by the Illuminati and, back in the real world, scientists are already concerned about brainjacking.

Potential threats range from remote battery draining or tissue damage, all the way through to sensory, motor or emotional manipulation. And, if our implants are wired up to the internet, they might also end up plumbed into ever advancing artificial intelligences. And who knows where that could lead.

Spartan vs splicer

Chances are, human 2.0 will be both spliced and augmented, but which is better, and whether either a good thing is up for debate.

Splicers risk unpredictable genetic side-effects, whilst Augs wrestle with rejection and repeated upgrades. Genetic engineering could completely change our species and tech enhancements could take us over the line that separates man from machine.

Bioshock ended in the collapse of civilisation, the Augs in Deus Ex were relegated to slums, and Halo's Spartans are soldiers locked in an impossible war.

We're hoping human 2.0 turns out better for us than for our video game heroes.