Get all the latest news, reviews, deals and buying guides on gorgeous tech, home and active products from the T3 experts

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The T3 Hot 100 2015

Welcome to T3's Hot 100 – the ninth annual celebration of the best tech movers and shakers that we expect to burn brightest this year and beyond. It's the ultimate cutting-edge wish list, unveiling the gadgets, innovations, trends, brands and burgeoning talent that are igniting our imagination and preparing to take the tech world by storm.

No rumours, no speculation – everything on the list is a nailed-on certainty, either right now, this year or next, from super phones to space tourism, and even a dash of huge tech personalities to boot.

If you're looking for more awesome tech, check out 10 things you need to know about self-driving cars

Apple Watch

It's the most anticipated gadget of the year, if not the decade. So is now the time for Apple to conquer wearable tech?

There was a strange period a few years back when we found ourselves on the tube, sniggering at the first guy we'd seen using an iPad in public. It was a pretty awkward moment, but it didn't take long for iPads to find their way into the public consciousness.

We suspect that the story will repeat with the Apple Watch. Like the iPad, this isn't an entirely new device, but it's a very Appley take on something that's been around for a while. With an initial run of five million units, the company must be feeling pretty confident in its debut piece of wearable tech.

Not that it can do much wrong, really. Pebble proved that people were interested in wrist-attached screens, while Fitbit's tracking tech has reduced the wobbliness of many bums around the world – but both of these pieces of wristborne tech have remained fairly niche. Android Wear, Apple's biggest competitor in this field, has suffered a disastrous year, with just 15% of wearables sold running Google's wrist-orientated OS. Fragmentation of the devices combined with poor marketing are probably to blame here.

Apple solves this by giving us fundamentally the same watch, and the same experience, in a variety of different guises. The Apple Watch Sport model is available for fitness freaks. The Apple “Edition” is the most notoriously expensive. And for everyone else, there's the bog-standard Apple Watch. Two screen sizes are available: 38mm and 42mm, and while the watch is still bulkier than your average piece of wrist jewellery, Apple has gone to great lengths to ensure that it looks sleek and attractive, while enabling just enough customisation to make it feel like it's truly your own.

Apple's also re-thought the way we interact with a wrist-attached device. You can glance at the screen and get instant notifications, and rather than dumbly sticking a vibrating motor in the device it includes a Taptic Engine, which is described as a “linear actuator”. This basically means that alerts you receive on the watch will trigger what feels like a small tap on the wrist. Apple believes that each alert will become recognisably different. It will even pick up your heartbeat and broadcast it to your loved one – if they've got an Apple Watch, of course.

Also, the addition of GPS and an accelerometer turns it into a sports watch capable of monitoring your current activity. The Apple Watch will make headlines for years to come, and is a worthy number one in our Hot 100.

£299-£9,500 | APPLE.COM | OUT APRIL 24

Electric Vehicles

Finally, our reliance on petroleum appears to be combusting. Major automobile companies – BMW, Honda, Nissan and Mercedes-Benz – are making all-electric cars. Meanwhile there are rumours even Apple is looking to get in on the clean vehicle act. It's either going to make an electric car, or the next iPhone's going to be really, really big. And have wheels.

The most important element here is the infrastructure, though – you can have all the electric cars in the world, but if you run out of juice 100 miles from anywhere, the movement is going to lose its appeal. Fortunately governments have caught on to the sea change, deploying charging stations at regular intervals around the country. Tesla's battery swap system (Model S pictured) should make for faster recharging, too, and another benefit of electric cars is that you can charge them at home. If you need further proof that is the way forwards, just look at Porsche – the sportscar manufacturer is set to unleash an electric car in 2019. And we can't wait for that.

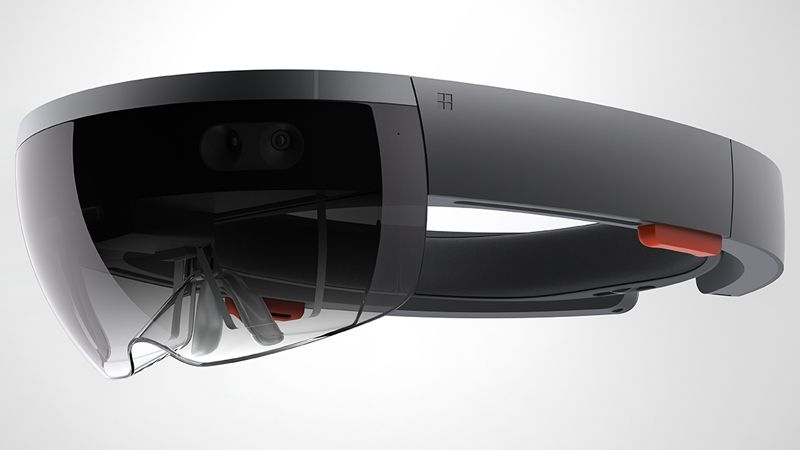

Microsoft Hololens

Microsoft is like an eccentric drunken old lord, spending money on crazy side projects. The craziest of these is HoloLens. The bastard child of Oculus Rift and Google Glass, this augmented reality headset overlays your view of the world with virtual elements, so your living room can become a Minecraft world, with three-dimensional craters in your coffee table and bat-filled holes in the wall. The crucial difference between this and Oculus Rift is that you'll be able to actually see the real world, rather than feeling completely isolated.

£TBC | MICROSOFT.COM | OUT TBC

Android OS

Android has dominated the gadget scene for a few years and has recently gone on the offensive. Lollipop is the mobile OS you've always dreamed of. Then there's Android TV, looking to revolutionise the smart TV scene, with Sony and Philips signed up. Android has also taken to the roads with Auto, hitting an in-car entertainment system near you soon, offering satnav, seamless integration of your music and much more.

LG

2015 could be the year LG comes of age. Its G Flex 2 smartphone will take bendy phones beyond novelty. Meanwhile, its flagship LG G4 will push mobile screen resolutions to their current limits, and new TVs boast 8K and 4K quantum dot resolutions. But its most important moves are behind the scenes: it's developed its own mobile processor, potentially for use in its G4 phone, and it's providing screens for Apple Watches.

G FLEX 2, £500 | G WATCH R, £199 | G PAD 10.1, £199

HTC One M9

A couple of years ago it looked like HTC was down on its luck, unable to compete with apple and samsung. It's bounced back in a big way, though, wisely spending money on marketing and consolidating its once-vast product range into the one series, which began in 2012. And the most recent iteration – the HTC One m9 – is by far the best yet.

This smartphone wisely drops the misunderstood 4-megapixel ultrapixel snapper of its predecessor in favour of a 20-megapixel sensor. While HTC's partnership with beats ended a while ago, the one m9's speakers still deliver a wide soundscape. Within, there's an octo-core snapdragon 810 chip and 3gb of ram to keep things running smoothly. It's the premium aluminium chassis that has already made it a contender for t3's smartphone of the year, though.

FROM £549 | HTC.COM | OUT NOW

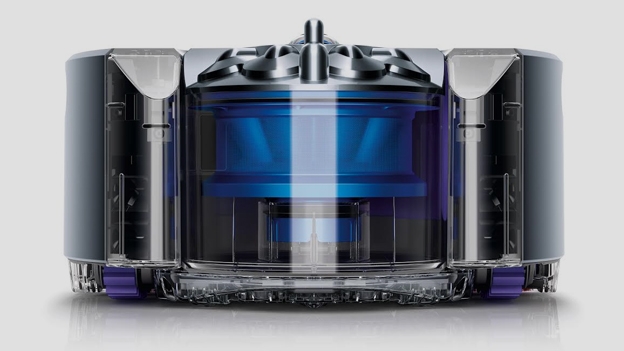

Dyson 360 Eye

The Dyson 360 Eye is a vacuum terminator. A 360-degree camera lens means it immediately knows where to clean. There's also uber-powerful cyclone suction tech and tank tracks.

£TBC | DYSON360EYE.COM | OUT TBC

BMW i8 Concept

As far as planet-saving cars go, BMW has nailed it. Not only does the BMW i8 look like a shockingly beautiful concept that somehow made it beyond the drawing board, it also has sensational supercar-esque performance, with a 0-60 of just over 4 seconds. It's green too, with an efficient petrol/electric engine and lightweight, aerodynamic body promising 135mpg. It's packed with smart features too, such as laser LED headlights – no, really. It's genuinely a step in the right direction for the motoring industry; less oil-dependent, while still remaining fast and cool (and looking it).

Samsung Gear VR

It's the year virtual reality finally goes mainstream, and Samsung's nifty headset is first out of the blocks in commercial terms. It has limitations as you'd expect at this stage – such as a limited library of content and it needs to be paired with a Note 4 (or with the new version, the S6). But it's a great showcase for virtual reality right now. It may not have the longevity of the Oculus Rift, but it'll certainly play a valuable role in pushing virtual reality into the mainstream. Couple it with the all-important smartphone and you've got an instant new world of awesome interactiveness.

£169/£199 (WITH GAMEPAD) | SAMSUNG.COM | OUT NOW

Vinyl

Neil Young might reckon it's a fashion thing, but then Rusty's got his Pono music player to promote. The truth is, vinyl is surging. Sales topped a million in the UK in 2014 and pressing plants can't keep up with demand. There's another argument that says it's purely about nostalgia for some sort of imagined audio superiority, but when 20-somethings who have never bought a vinyl record before are raving about its warmer sound, you've got to wonder.

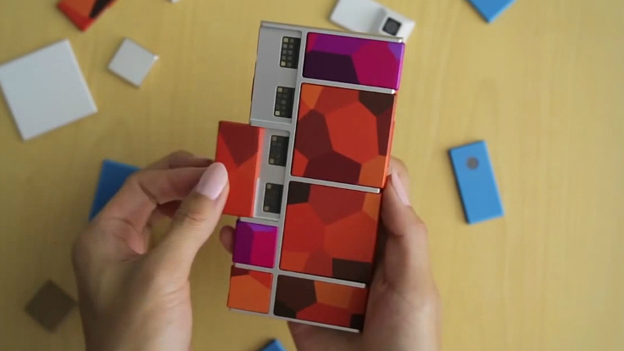

Project Ara

Google recently showed off its latest prototype of the modular mobile, complete with hot-swappable components. This means, for example, you can pick the camera for your phone rather than your phone for its camera. The future of mobiles? Wait and see.

£TBC | PROJECTARA.COM | OUT AUTUMN

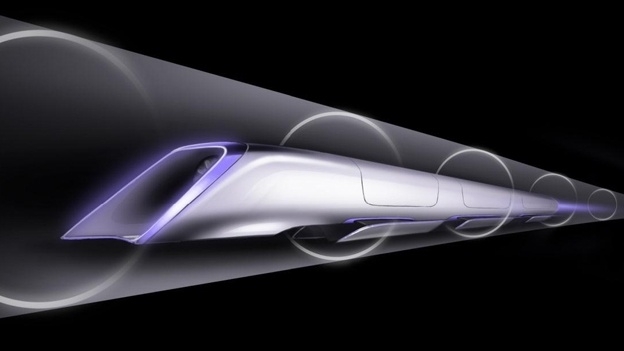

Elon Musk

Musk's company Tesla recently improved one of its models' speed just by issuing an over-the-air update. He plans to build a test track for his bonkers Hyperloop transport system which is said to propel people at 700mph. What a busy boy...

Sony PlayStation 4

Sony went and one-upped the Xbone using its PS4-exclusive card, releasing PS3- classic The Last of Us in big-screen 1080p remastered glory. The PS4 Anniversary Edition released this year was ace, and the new version of Project Morpheus looks to change the way we play.

£299 | PLAYSTATION.COM | OUT NOW

Google Glass 2.0

When Google announced it was pulling Google Glass from its Play Store, the world thought the days of the glasshole were numbered. Not so. Glass lives on and now has a dedicated team rather than being a part of the Big G's renowned X Labs.

PRICE TBC | PLUS.GOOGLE.COM/+GOOGLEGLASS | OUT TBC

Nest Learning Thermostat

The world's best smart thermostat is now so much more. It works with products made by Philips, LG, August and UniKey, among others, to become the brains of your smart home. It's your start to the easy life.

It's also possibly the first truly successful and practical solution to the oft-promised but still strangely elusive 'connected home'. The smart central heating system is a start, but throw in smart smoke detectors and alarms, washing machines, cars that can 'call ahead' to activate Nest, and even that old stand-by the self-closing curtain, and you're well on the way to what Tomorrow's World was always dreaming about in the 1980s.As time goes on, Nest will only become more ubiquitous, being planned and built into new housing developments from

the ground up (quite literally).

£180 | NEST.COM | OUT NOW

Apple MacBook 12-inch

Behold the 12-inch MacBook. It's fanless, super-compact and with a Retina Display, it's stunning. We can't wait until April to get our hands on it.

from £1,049 | Apple

LG 77EG9900 UHD 4K TV

Let's face it, if you're gonna go 4K you might as well go big with it. With LG's whopping 77-inch 'flexible' OLED TV you can actually alter the degree of screen curve to suit who's watching.

£SILLY MONEY | LG.COM | OUT SEPTEMBER

From Apple to Google: Tony Faddell

It has been something of a year for Tony Fadell, the man who founded Nest Labs – purveyors of connected thermostats and smoke alarms – after leaving Apple. For many people, working for Apple – and indeed being one of the founding fathers of the iPod – would be considered the pinnacle of a career, but Fadell has continued to enjoy success in other, new areas.

It was certainly a bumpy start for Nest's range of products, but even a series of security concerns didn't dissuade Google from snapping up the company for $3.2 billion. And now it's flying.

Despite the acquisition, Nest Labs has been left to do its own thing, focusing on its core products and working with the likes of NPower in the UK to get its smart thermostat into as many consumer homes as possible. Fadell, however, has very much been taken into the Google fold – and who could blame them?

He has been placed in charge of the Google Glass team in the hope he will be able to bring the project out of the shadows, creating the much-anticipated Glass 2.0 and transforming the project into a mainstream success.

Used to working with Steve Jobs, you could say that Fadell is more than equipped to handle working for Larry Page.

Yes, Google Glass may no longer be publicly available, but the project is far from dead, and Google hopes Fadell will be able to work the same magic on its wearable as he has on other projects.

He has something of a task on his hands to turn around the public image of Google Glass. A lot of negative feeling sprang up around the look, the cost and the limited availability of the device, and this is something that will need to be addressed. Based on Fadell's track record, he could be just the man to do it.

The entrepreneur is looking to completely redesign Glass after the original product came in for criticism. He's now working alongside Ivy Ross and there have been suggestions the second version of Google Glass will feature a completely new design.

Fadell's previous work at the ever-secretive Apple should prove useful here, too. While the first generation of Glass was a very public beta, this time around things are being kept behind closed doors until they're truly ready.

Vaio Z Canvas

This 12.3-inch portable PC comes with a detachable keyboard to transform into a tablet, as well as a stylus for direct interaction with the touchscreen. A jack of all trades.

£TBC | VAIO.COM | OUT MAY (IN JAPAN)

HP Sprout

The Sprout: it's a PC! It's a (3D) scanner! It's a projector! It's a projection surface! This “workstation” is great for both creatives and children alike.

£1,899 | HP.COM | OUT NOW

Lightning LS-218

No internal combustion engine in sight – this is all electric. 218MPH and instantaneous surge whenever you want it. You can even get up to 180 miles to a charge.

$38,888 | LIGHTNINGMOTORCYCLE.COM | OUT SOON

Beats Solo 2 Wireless

Musical purists might scoff at their bass-hungry approach, but Beats' follow- up to the all-conquering Solo are the only cans to be seen wearing if you're in the least bit “street”. The fact they're now wireless means you can bust even more moves... homie.

£270 | BEATSBYDRE.COM | OUT NOW

Lytro Illum

Imagine a stealth version of a regular bridge camera or DSLR, complete with a matte black paint job, and you have the Lytro Illum, a device for creating what are termed “living images”. You can alter the perspective or focus point even after the shot has been taken by tapping the display.

£1,299 | LYTRO.COM | OUT NOW

Cambridge Audio CX Series

Audiophile-grade sound meets cutting-edge minimalist design with Cambridge Audio's latest range of network streamers, amps and AV receivers. Beautiful, with the sound quality to match.

£VARIES | CAMBRIDGEAUDIO.COM | OUT NOW

Samsung Galaxy S6

Samsung's previous Galaxy phones weren't exactly primitive, but with the S6 it is taking on all-comers in terms of tech, features and battery life. All this in a stunning all-metal design, too.

£TBC | SAMSUNG.COM | OUT NOW

Apple iPhone 6

Helping Apple to amass a huge fortune, the iPhone 6 continues to be the world's most in-demand smartphone. It's unquestionably the best iPhone Tim Cook and co have ever made.

FROM £539 | STORE.APPLE.COM/UK/IPHONE | OUT NOW

Parrot Bebop

Parrot's Bebop Drone gives you the ultimate mini flying experience. With up to 2km of range, you can pilot the 1080p camera-equipped drone anywhere, and you can even see what the camera sees.

£720 | PARROT.COM | OUT NOW

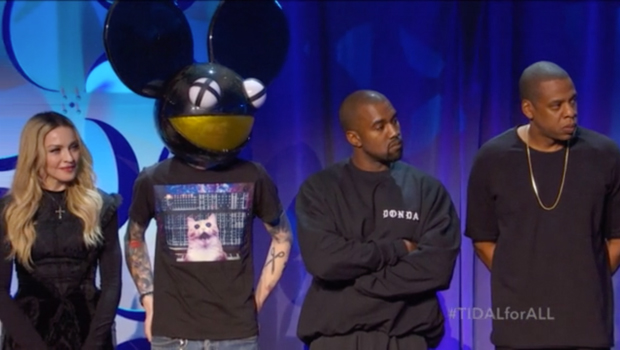

Tidal

Tidal gives music-lovers a new kind of streaming experience, with lossless 1411kbps files, enabling you to listen to your favourite tracks at CD quality over the web. Nice.

£19.99 PER MONTH | TIDALHIFI.COM | OUT NOW

Pebble Steel

Sure, the Pebble Steel doesn't have an all-singing, all-dancing colour touchscreen, but it's refined and a joy to use. And it's compatible with iOS and Android.

£179 | GETPEBBLE.COM | OUT NOW

Alienware Alpha

Steam Machines have become hot property. This mini-PC plugs into your TV, giving you access to the games on your account. Being speedy, it'll run the latest titles at a decent lick.

FROM £429 | ALIENWARE.CO.UK | OUT NOW

Oculus Rift

Not content with scaring the bejezus out of anyone donning it, the company behind the virtual reality headset has branched out into films. The future of film is interactive.

£TBC | OCULUSVR.COM | OUT TBC

Apple HomeKit

A unifying standard aimed at developers and home automation companies, HomeKit is designed to let you control everything from your heating to your toaster via your iPhone.

PRICES TBC | DEVELOPER.APPLE.COM/HOMEKIT | OUT SUMMER 2015

Imagination Creator CI20

Fancy yourself as a budding Steve Jobs, but don't want to blow your garage up? Then Imagination's Creator CI20 is for you. This simple board is all about teaching newbies how to code – and taking on the ace Raspberry Pi too.

FROM £50 | IMGTEC.COM | OUT NOW

Space X

This Elon Musk venture plans to beam the internet via satellites, to parts it can't currently reach. Google recently backed it to the tune of $1 billion. We're not investment experts, but even we know that's a very good sign.

SPACEX.COM | OUT TBC

Apple Pay

Using your phone to pay for a pint will always be preferable to sorting through shrapnel. Praise be, then, for Apple Pay, which utilises the iPhone's Touch ID scanner. It's due to launch in the UK by the end of this year.

FREE | APPLE.COM/APPLE-PAY | OUT LATE 2015

Wearable tech comes of age: Steve Mann

The father of wearable tech on google glass, and living in a world where humans have the same rights as buildings.

T3: When did you start creating wearables?

Steve Mann: My grandfather taught me to weld when I was just four years old, and I became interested in being able to see better, over a wide range of light levels. This is what led me to the invention of Digital Eye Glass (wearable computing) and HDR (High Dynamic Range) Imaging (see wearcam. org/hdr.htm).

I was always looking for a place where I could combine my talents in art, science, technology, mathematics, and inventrepreneurship (inventorship and entrepreneurship). I ended up getting accepted at MIT so I brought much of my wearable computing with me. I was my own walking laboratory, TV station and photographic studio.

T3: How was it received at MIT in the 1970s? The ideas must have been fairly forward-thinking.

SM: Certain others were initially opposed to my new concepts, and wearable computing in general, but later took these ideas as their own, by publishing my Sixth Sense and Wearable Computing work without any attribution.

T3: Did you ever envisage then that the tech industry would be following behind you in 2014/15?

SM: Yes, I did envision that industry would catch on to these ideas of HDR Imaging, Wearable Computing and Humanistic Intelligence.

I was a bit disappointed by some of the results of the tech industry, and how long it took the industry to catch on. In the 1970s, I envisioned a convergence of PC, camera, and phone into something that could be worn, and I embodied it as a viewfinder in the upper right-hand corner of my vision. By 1998 I came up with a more sleek and slender eyeglass.

T3: Just like Google Glass then. Was Google aware of this?

SM: From early on, while still at MIT, I'd shown my work to Mark Spitzer who founded MicroOptical, making eyeglasses after my early 1990s eyeglass-based wearable computer, but he didn't include any camera, or see the need for it. I explained to him the importance of having a camera – for example to do AR, so it would be more than just a display – and he eventually caught on to some of the more important ideas of computer-mediated reality I was working on. Then Google purchased his company.

T3: But Google must have blown your technology away, right?

SM: When Google was trying to come out with its product it hired some of my students and were probing around my work, and came up with a design quite similar to my 1998 system, but with the essential form of my 1970s embodiment – the little viewfinder.

T3: So how would you rate Google's effort?

SM: I thought that being a big company they'd come up with something more advanced.

It was kind of funny in 2014, when I was wearing my 1998 EyeTap, people would say “Is that Google Glass?” and I'd have to remind them it was a project I'd completed before Google even existed.

T3: And did you think Google Glass would fail?

SM: I predicted the downfall of Glass as a product in my IEEE Spectrum article in 2013. I came to realise that the industry wouldn't 'get it right' unless I took a more active role, so this is where my work in inventrepreneurship started to take on some importance. We just raised $23 million in a Series A investment round for Meta Spaceglasses, as I think that it's very important for inventors to be involved along the entire flow from idea to product.

The kind of vision needed to create new inventions is also integral to product design.

T3: You've been photographed with and used some fairly obtrusive wearables. Have you received extreme negative reactions?

SM: What I noticed is that while the early peer opposition subsided, most of the remaining opposition came from businesses such as restaurants and department stores. Ironically, the more surveillance they had in their business, the more scared they were of someone wearing a camera.

T3: Why should we wear cameras on our faces and bodies?

SM: A person is responsible for their actions. With those increased responsibilities, a person ought to be allowed to see, and to remember what they see. It's quite absurd, really, that buildings and cars are always allowed to 'wear' cameras but people sometimes are not. My children say that they hope to live in a world where human life is no longer valued as less important than the well-being of cars and buildings.

LG G Watch Urbane

With the Urbane, LG has taken its G Watch R and made it even better. An all-metal design is paired with a stitched leather strap, but specs are the same as the Watch R. The Korean company is aiming it squarely at the Apple Watch.

£299,99 | LG.COM | OUT NOW

Myo

A gesture-control armband that actually harnesses the electrical activity of your muscles (no implants necessary, fortunately). Strap it on, hook it up to your phone or laptop via Bluetooth, and use Myo apps to CONTROL THE WORLD. Or just, y'know, your kit.

$199 | THALMIC.COM | OUT NOW

Netflix

With Better Call Saul, House of Cards series three, Marco Polo, and Orange is the New Black series three, Netflix has nailed it with the original series this year. It's also going into films, with a sequel to Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon.

£5.99 A MONTH | NETFLIX.COM | OUT NOW

Mcintosh MHP 100 Headphones

These cans will empty your wallet, nay bank account, of £2,000. But if you must have the best, then you're in the right place – these feature Tesla annular neodymium magnet motor assemblies, which give you an incredible range of sound.

£1,995 | MCINTOSHLABS.COM | OUT NOW

Sony 4K Action Cam

Able to shoot 4K at 30fps, 1080p at 120fps and 720p at 240fps, the 4K Action Cam is perfect for slo-mo footage. Add to this the 170-degree wide-angle lens and the built-in mic with noise and wind reduction, and you have a device that should have GoPro trembling.

£359 | SONY.CO.UK | OUT NOW

Porsche 918 Spyder

The 918 Spyder is Porsche's sublime take on the petrol-electric model, with 874bhp, a top speed of 210mph and an electric-only range of, er, 12 miles. Get your bids in – only 918 are being made.

AROUND £712,000 | PORSCHE.COM | OUT NOW

iMac with Retina 5K Display

Not content with 4K, Apple upped the ante when it released this update of its popular all-in-one back in October last year. You may ask “But no one needs 5K, do they?” Well, maybe not for a TV, but for creative professionals using a computer, the more pixels the better. Hence this, Apple's flagship machine, with a gorgeous 27-inch edge-to-edge display.

This top-end model also features a quad- core Intel Core i5 or i7 CPU, up to 32GB of RAM, a 1TB/3TB Fusion Drive and an AMD Radeon R9 M290X with 2GB video memory. Delicious and surprisingly affordable.

FROM £1,999 | APPLE.COM | OUT NOW

Veolo 4K

Pairingtop-quality hardware with smart UI design, the A.C. Ryan Veolo 4K is the ideal media player for playing Ultra HD content in your lounge. Huge format support makes it hugely enticing.

£140 | VEOLO.COM | OUT NOW

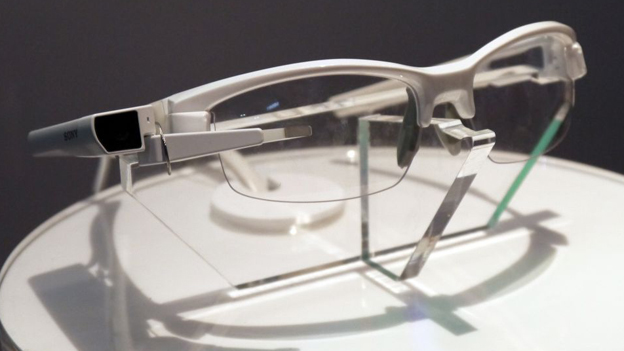

Sony SmartEyeglass Attach

This head-mounted display is designed to clip onto existing specs. A tiny prism in front of the right eye does the business, fuelled by data from a phone or similar.

£TBC | SONY.COM | OUT 2015

Skype Translate

The new version of Skype will enable you to have video calls with others speaking different languages and will translate your (and their) spoken language, on the fly.

FREE | SKYPE.COM | AVAILABLE SOON

BeoPlay

Whilst Bang & Olufsen continue to develop high-end audio kit for the home (see the luscious BeoSound Moment, for example) it's the BeoPlay (or B&O Play, if you like) range that has really seen the company soar in the last year. The BeoPlay A2 Bluetooth speaker – being a slickly designed, portable yet powerful device – has become the company's fastest-ever selling product. Its range of high-quality headphones, including the noise-cancelling wireless H8s, also impress, as does the brand new Beolit 15. B&O is at the forefront of designer tech.

£VARIES | BEOPLAY.COM | ALL PRODUCTS OUT NOW

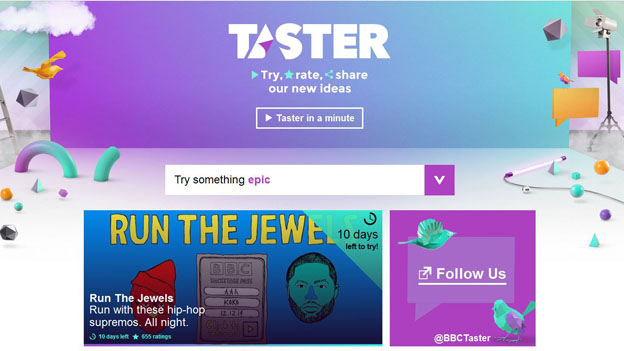

BBC Taster

The Beeb's Taster turns you into a beta tester for its newest ideas. The site is chock with videos for shows, including interactive strands, which can be rated, potentially ending up on the telly.

FREE | BBC.CO.UK/TASTER | OUT NOW

Ampy

This Kickstarter project is the world's smallest wearable motion charger – a 1,000mAh battery that is charged by movement such as running or walking. The more you do, the more spare juice you have on hand.

$95 | GETAMPY.COM | OUT JULY

Hammerhead

The Hammerhead One is, in effect, a GPS for cyclists. The gizmo uses LED light signals to guide you, as well as providing headlights and long battery life via your phone's Bluetooth. Nice.

$85 | HAMMERHEAD.IO | OUT SPRING

Alcatel Onetouch Watch

This smartwatch comes in a range of styles, is packed with sensors and works nicely with iOS and Android. Of course it keeps tabs on your fitness too. Nice to see a smartwatch that fits around you rather than the other way around.

£100 | ALCATELONETOUCH.COM | OUT NOW

Vantage GT3

It's already too late to order one of the 100 Aston Martin Vantage GT3s being produced. It's a shame you'll never get your hands on the mindblowingly-powerful 6-litre V12 engine, titanium exhaust, 595bhp and ultra-lightweight carbon-fibre structure that makes this motor so desirable. Still, there's always eBay Motors.

£250,000 | ASTONMARTIN.COM | ALL SOLD

Onkyo and Dolby

Dolby's cinema surround system provides audio from overhead speakers, and now owners of 2014 Onkyo AV receivers can get in on the act with a firmware update enabling Atmos on any surround speaker set-up – and it works with existing Blu-rays too.

FREE UPDATE | ONKYODOLBYATMOS.COM | OUT NOW

Avegant Glyph

Is it a virtual reality headset? Is it pair of noise-cancelling headphones? Well, actually, it's both. When not lost in virtual worlds, flip the headband up and listen to some beats. The most subtle – and possibly most handsome – VR headset there is.

$599 | AVEGANT.COM | OUT AUTUMN

Smarter Wi-Fi Coffee Machine

You don't need to get up to start the coffee brewing thanks to this nifty device. Just open the app and set it from your phone. Then get up when it's done. Essential on cold mornings – or “summer” as it's also known.

£129 | SMARTER.AM | OUT NOW

Nintendo 3DS

The brand new models of the Nintendo 3DS and 3DS XL feature more buttons for greater control, face tracking for more immersive 3D, and some rather cool replaceable face plates (just like a Nokia circa 1998). Perfect for that “just one more go” on Mario Kart.

FROM £149 | NINTENDO.COM | OUT NOW

Samsung WAM

The Samsung WAM – Wireless Audio Multiroom – is the umbrella term for Sammy's speaker products and hub, designed for high-quality, er, multiroom audio. Set-up is made as simple as possible and you can stream from just about anything via iOS or Android.

£50 HUB | SPEAKERS FROM £160 | SAMSUNG.COM | OUT NOW

Fitbit Surge

The prolific smartband maker's first smartwatch packs a heart rate monitor, whopping seven-day battery life, notifications, music controls, sleep tracking and alarms, all on top of all the usual fitness gubbins. No wonder it's referred to as a fitness super watch.

£199.99 | FITBIT.COM | OUT NOW

Parrot RNB6

Apple CarPlay and Android Auto are all well and good, but what happens when you change your phone (as we know you often do)? This in-car system flicks between the operating systems with one button, so you won't need to buy a new car every time your upgrade your handset. Shame.

£TBC | PARROT.COM | OUT TBC

Naim Mu-so

Naim has a solid reputation for creating fantastic home audio systems – and its Mu-so is no exception. Looking like Batman's home music system, it streams from your phone, tablet or laptop. And it has more connections than a record label bigwig. As you'd expect, it sounds sweet as.

£895 | NAIMAUDIO.COM | OUT NOW

Samsung Gear VR in-flight

Flying to Oz is one of the most tedious experiences you can endure – unless you're flying in Qantas' First Class cabin. The airline has teamed up with Samsung to offer Gear VR headsets to passengers, offering the ultimate in escapism.

AVAILABLE TO FIRST CLASS QANTAS PASSENGERS NOW

Samsung Galaxy A7

Samsung has gone metal mad of late, and this is its range-topping smartphone (available as we type this, anyhow). It boasts a monstrous 5.5-inch screen, two quad-core processors and enough RAM to fell an elephant. Plus at 6.3mm thin, it's Sammy's slimmest phone ever.

FREE ON CONTRACT | SAMSUNG.COM | OUT NOW

Withings Activité Pop

The Withings Activité was a real game- changer when it was released last year – a fitness tracking device with the style and accuracy of a Swiss timepiece. But at £320, it certainly isn't a cheap option. The recently launched Pop has the same fitness and sleep tracking skills as the Activité, but costs a whopping £200 less. And all with slightly less “premium” materials (with the same stylish looks). What time is it? Probably time to get a new watch.

£119.95 | WITHINGS.COM/UK | OUT NOW

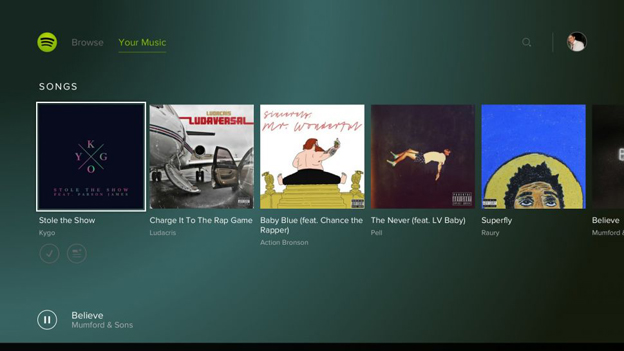

Spotify on PS4

Big S has binned its Music Unlimited service and replaced it with PlayStation Music,a new service with Spotify at its heart. Link accounts to stream tunes while playing games.

£9.99 P/M | SPOTIFY.COM | OUT NOW

Citymapper

With absurdly detailed transport routes, breezy location sharing and a growing number of cities, there's simply no other app as good as Citymapper at getting you home after a night out.

FREE ON IOS AND ANDROID | CITYMAPPER.COM | OUT NOW

Cubify Ekocycle

Although best known for his music, there's more to the man that is Will.i.am. The tech entrepreneur recently had a stab at the wearables market and he's also come up with this rather snazzy 3D printer, courtesy of Cubify. What makes it unique is its ability to print using filament constructed (partly, we might add) from recycled plastic bottles, so you can get your plastic fix without getting a phone call from Greenpeace each time you press print.

£939 | CUBIFY.COM | OUT NOW

iPad Pro

OK, this is pure speculation, we know, but at the time of writing this there has been significant leaks suggesting Apple is working on a 12-inch version of its all- conquering tablet for business and pro creative users. If it materialises, it will no doubt be a huge seller.

PRICE TBC | APPLE.COM | OUT TBC

Wharfedale 200 Diamond Speakers

Losing yourself in a Brian Wilson-esque quest for perfect sound is never a good look. Nor will it do your wallet any favours. These speakers, however, strike the perfect balance. They won't leave you penniless, but will make Pet Sounds sound perfect.

FROM £199.95 PER PAIR | WHARFEDALE.CO.UK | OUT NOW

Windows 10

The upcoming OS is loaded with the ace Cortana voice assistant, split desktops for work and play and makes apps work quickly and seamlessly between devices.

PRICE TBC | MICROSOFT.COM | OUT LATE 2015

Uber

After raising billions from investors, taxi firm Uber is now splashing cash to create the Uber Advanced Technologies Centre. This new Pittsburgh institute will work specifically on driverless cars. Total Recall- style cabs are getting closer...

UBER.COM

Nokia N1 Tablet

Nokia's first device since selling its mobile arm to Microsoft looks rather like an iPad Mini (well, exactly like it, actually) but its skill set is all its own – swipe gestures as a shortcut to contacts, apps and the like, and it predicts which app you'll open next. Interesting.

£TBC | N1.NOKIA.COM | OUT TBC

Prynt

This rather innovative phone case lets you print snaps directly from your smartphone, just like an old-school Polaroid camera. It uses ZINK (Zero Ink technology) so there's no pricey ink cartridge to refill. Just stock up on special paper, and get posing.

$99 | PRYNTCASES.COM | OUT OCTOBER

Facebook at Work

Soon, randomly liking posts and trawling friends' timelines will be legitimateinoffice time. Facebook at Work is an attempt to wrest control of the workspace from startups like Slack.

FACEBOOK.COM | OUT 2015

Music Fidelity Merlin 1

The Merlin 1 is a pretty neat (and powerful) home audio system, combininga Bluetooth streamer with digital amplifier, turntable and custom speakers.

£1,300 | MUSICALFIDELITY.COM | OUT NOW

Immersis

This turns your lounge into an IMAX, so you'll never have to play virtual reality games on your own. It projects the image onto your wall, and resizes it depending on the room size.

$2,500 | IMMERSISVR.COM | OUT OCTOBER

Xiaomi Mi Note Pro

Xiaomi has come from nowhere of late to challenge Apple for smartphone supremacy. The Mi Note Pro is its take on the iPhone 6 Plus, with a 5.7-inch QHD screen, 13-megapixel camera and a whopping 4GB of RAM. It's highly affordable, too.

3,299 YUAN (£347) | MI.COM | OUT MARCH

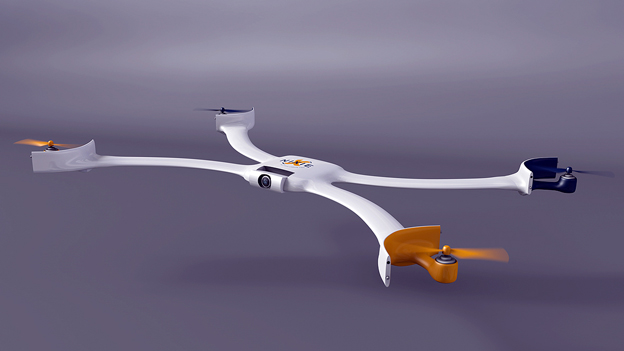

Nixie Drone

Clip this mini drone to your wrist and, when you want, it can fly off and take pictures of you – whether you're rock- climbing, slacklining or simply playing footie with the kids. It's a pretty neat little gadget, and far more socially acceptable than a selfie stick.

£TBC | FLYNIXIE.COM | OUT TBC

Montblanc E-Strap

The Montblanc e-Strap combines the best of both worlds, giving you the mechanical accuracy and appeal of classic Timewalker timepiece along with the convenience of a smartband – enabling you to look the part but still keep connected on your travels. The E-Strap on the device is interchangeable, meaning it can fi t on selected Timewalker watches, and features an activity tracker, smart notifications, remote controls and more. It connects via Bluetooth to a number of Android and iOS smartphones. Expect other luxury watch manufacturers to follow suit soon.

PRICE TBC | MONTBLANC.COM | OUT JUNE

Razer Nabu X

Fitness trackers don't have to cost the earth – as proved by the excellent Razer Nabu X. This one replaces the LCD with LEDs (a great way of cutting costs) but still lets you see your calories burned, steps taken, distance travelled and the rest. And it costs less than a night out.

£45 | RAZERZONE.COM | OUT NOW

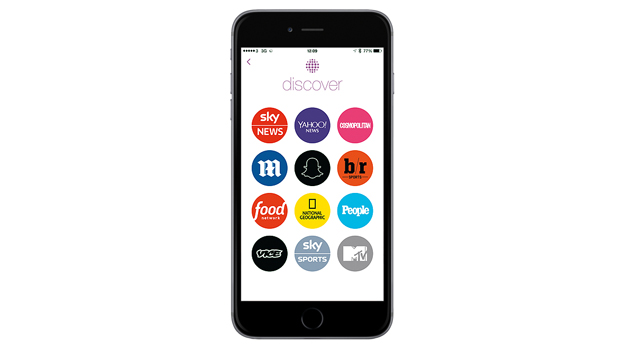

Snapchat Discover

Whereas Snapchat is undeniably a great way to communicate with friends (we'll ignore what you're thinking) the new Discover feature adds news and video from many different channels, including Sky Sports and CNN. All in a lovely interface.

FREE | SNAPCHAT.COM | OUT NOW

Mad Catz Lynx 9

Behold, the Optimus Prime of games controllers. It folds up neatly to fit in a pocket. It also works as a tablet stand. And, the Transformers-esque controller clips either side of your phone so it doesn't block the screen. It's the best mobile gaming control around.

£TBC | MADCATZ.COM | OUT TBC

HTC Re Camera

HTC's portable video star now has the ability to upload live to Youtube through the Android or iOS app. The mini shooter features a 16mp sensor that shoots 1080p, 30fps, FHD video, and can capture up to 1,200 16mp photos on a single charge. It's waterproof too – you can submerge it to 1 metre for up to 30 minutes. This is all well and good, as long as no one turns the camera on you unawares!

£129 | RECAMERA.COM | OUT NOW

Qardiobase

The QardioBase Smart Scale will recognise you and measure your BMI, body fat,muscle, water and more. It'll also show an angry face if you've eaten too many pies.

$149 | GETQARDIO.COM | OUT SPRING 2015

Freeview Play

The soon-to-be- released Freeview Play combines catch-up TV, OD services and liveTV. The service will be free and compatible with existing broadband services.

FREE | FREEVIEW.COM | OUT 2015

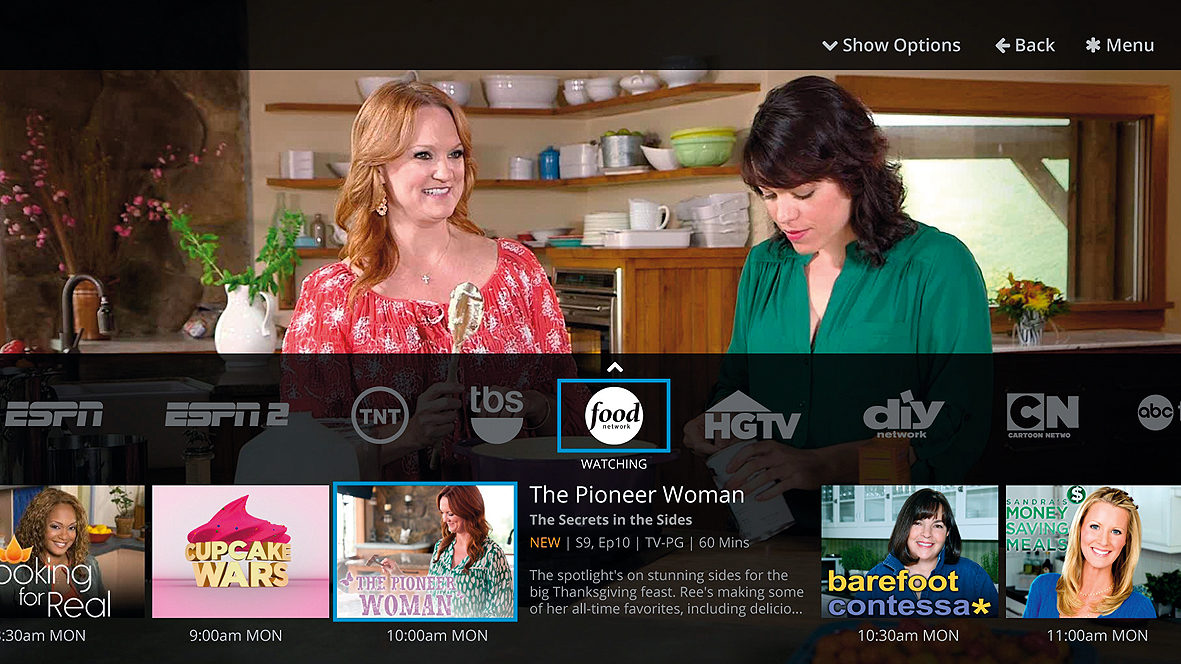

Sling TV

Sling TV enables you to subscribe to a myriad of US-only channels (at the moment)for$20 per month. All delivered over the Internet to your TV, PC or mobile device.

$20 PER MONTH | SLING.COM | OUT US ONLY

Canyon Projekt MRSC Connected

Modern race bikes don't have suspension, for good reason – it's heavy and wastes energy. With the Projekt MRSC Connected, however, the suspension units use Magneto-Rheological fluid, which changes consistency when it's exposed to a computer-controlled magnetic field. When you're on a smooth road it'll stiffen up, so none of your energy is lost, but hit a more rugged path and it loosens, resulting in a more comfortable ride.

PRICE TBC | CANYON.COM | OUT TBC

Samsung Galaxy Tab S

Short of spending every waking hour at an IMAX cinema, Samsung's Galaxy Tab S is the best way to treat your eyeballs to the latest entertainment. The Tab S is loaded with a Super AMOLED screen packing a 2560x1600 resolution – it's a display to die for. Other features include the ability to run two apps at once (called Multi-window) SideSync 3.0 (enabling you to view your smartphone screen and control it on your Galaxy Tab S) and a finger scanner with advanced security features. In short, it's pretty much the best alternative to an iPad there is.

FROM £279 FOR 8.5-INCH MODEL | £349 FOR 10.5-INCH | SAMSUNG.CO.UK | OUT NOW

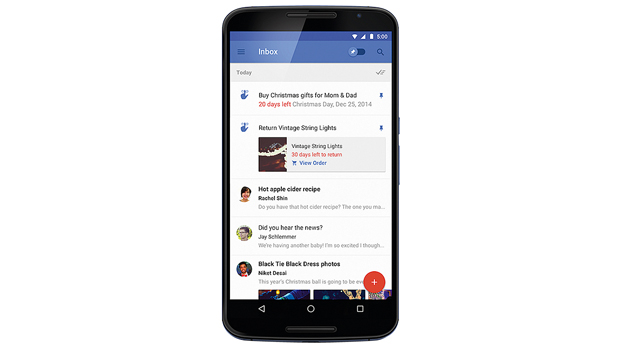

Inbox by Gmail

Aimed at bringing an end to email overload, Google's Inbox smartly groups together emails in 'Bundles' and makes everything much more visually arresting and less confusing than average mail apps. The invite only app should roll out properly by the end of 2015.

FREE FOR IOS AND ANDROID | GOOGLE.COM/INBOX | OUT NOW

Sky Mobile

Sky's never-ending quest to take over the world continues apace. Its deal with O2 owner Telefonica will see it offer mobile contracts from 2016, sold separately and as part of 'quad-play' packages with TV, landline and broadband. Expect enticing Sky Sports tie-ins to get you to sign up.

£TBC | SKY.COM | OUT 2016

Coolbox

This is the Swiss army knife of toolboxes. It packs a rechargeable battery for juicing up your phone, a dock and speakers, a whiteboard, tablet stand, LED lights for working in the dark and bottle opener for when the work is done. We'll drink to that. Cheers!

$299 | INDIEGOGO.COM | OUT JUNE

Mouse Box

Believe it or not, this mouse is an entire PC. Plug it into a monitor, and there's no need for your regular desktop machine. Also, it can flick between its own workings and your PC's desktop with one button, so you can pretend to be working when the boss approaches.

£TBC | MOUSE-BOX.COM | OUT TBC

Misfit Bolt

The Misfit Bolt is a wirelessly connected smart bulb. You can choose its colour to match your decor or even simulate sunrise by gradually lightening. Control it through the Misfit app and you will have smartened up your house no end. Misfit looks to be a big player in 2015 and beyond...

$49.99 | MISFIT.COM | OUT NOW

Misfit Flash

The days of playing second fiddle to the Misfit Shine are over. The Flash works with your Nest thermostat to set your heating, can start and stop your Spotify playlist, send messages to people using the Yo! app and more, and all at the touch of a button.

$49.99 | MISFIT.COM | OUT NOW

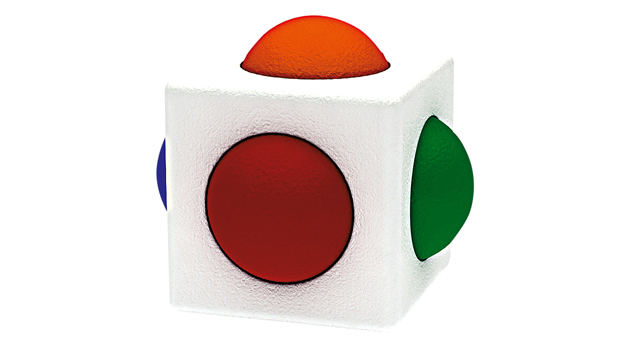

Skoog

Ideal for children or those unable to play normal musical instruments, the Skoog lets you make music by prodding, twisting and thwacking. It's wipe-clean, too.

£379.95 | SKOOGMUSIC.COM | OUT NOW

Flotsm

Flotsm, created by the co-owner of Rough Trade record shops, is a social tool aimed at those who want to be 'openly private', sharing ideas without the trolling.

£FREE | FLOTSM.COM | OUT OPEN TO BETA TESTERS

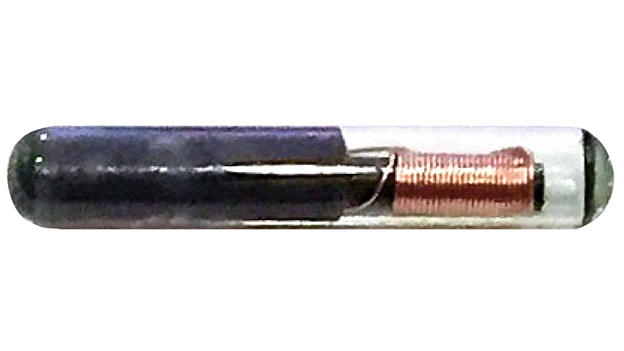

RFID Chips

Swedish technology campus Epicenter is now embedding RFID chips into staff, letting them open doors and operate printers. It could be coming to your office soon!

EPICENTERSTOCKHOLM.COM | OUT NOW

If you're looking for more awesome tech, check out 10 things you need to know about self-driving cars

Get all the latest news, reviews, deals and buying guides on gorgeous tech, home and active products from the T3 experts

For 25 years T3 has been the place to go when you need a gadget. From the incredibly useful, to the flat out beautiful T3 has covered it all. We're here to make your life better by bringing you the latest news, reviewing the products you want to buy and hunting for the best deals. You can follow us on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram. We also have a monthly magazine which you can buy in newsagents or subscribe to online – print and digital versions available.