Get all the latest news, reviews, deals and buying guides on gorgeous tech, home and active products from the T3 experts

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

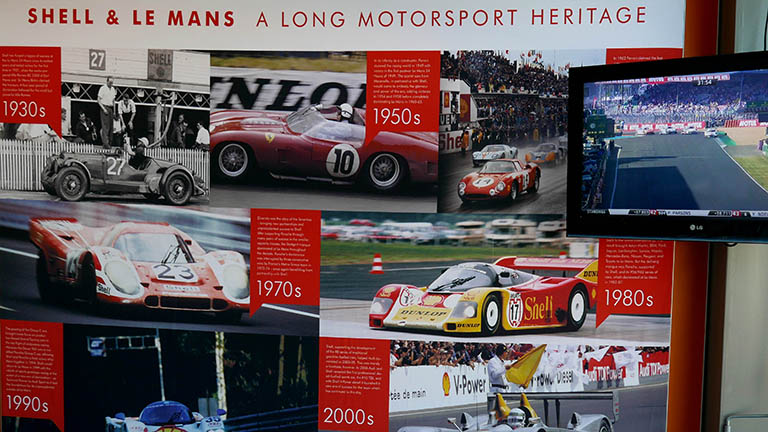

The 24 hours of Le Mans race, which has just completed its 85th year, is a legendary event.

And, for fuel suppliers, it’s also a vital part of the development process for products that end up in our everyday vehicles.

Since 2014, Shell has provided specially prepared V-Power gasoline (and diesel) to every competitor, with every year producing better performance and efficiency than the last. It’s therefore a vital part of the research and development process for Shell.

Le Mans race weekend provides them with enough data that’s equivalent to a full year of engine testing at the Shell Technology Centre back in Hamburg.

Mobile laboratory

As a result, the Shell mobile laboratory is one of the first vehicles on site at the race. It’s an immaculately turned out articulated truck, with a fully-fitted lab space inside. Both in the run up to the race and for the duration of the competition, the truck is staffed by a crack team of technicians. They keep monitoring and testing around the clock to ensure that pit crews are supported with the ultimate in quality racing fuels and oils.

The fuel tech

Peter Fordemann, Senior Key Account Manager Motorsport, is a seasoned pro when it comes to the event. “We supply 270,000 litres of fuel for Le Mans,” he says. “There are some leftovers from that, but you never really know what is going to happen. From my perspective, let’s say you think of it that 50 percent of the cars will finish, and 50 percent will not, and you never know when that’s going to be either.”

Unknown entity

The Shell man clearly loves his fuel and Le Mans has a special place on the racing calendar. “In terms of excitement for us, I would say it was the diesel we used in the 2006 race,” he ponders, selecting one of many highlights over the years. “I’d been with Shell for five years at that point, then heard the news and it was like ‘You what? You want to win Le Mans with a tractor?!’ It was just so far away from what people were thinking at that time.”

Get all the latest news, reviews, deals and buying guides on gorgeous tech, home and active products from the T3 experts

Special blend

“The fuel we use at Le Mans isn’t something that’s available commercially,” adds Peter. “And has been developed in cooperation with the car manufacturers and the ACO (Automobile Club de l'Ouest), over the last couple of years. So it’s been specifically made for this application; endurance racing, the LMP1, LMP2 and GTE cars. We store the fuel in a single tank in Hamburg, and distribute it from there all over the world. It’s a single batch fuel as we call it. We blend it once a year, control the quality and ship it everywhere.”

Chicken and egg

So, what comes first, the engine or the fuel? “Well, ask a Shell person,” grins Peter, “and they’ll say the fuel. But this is a race that has always pushed the technological borders with its hybrids and twin hybrid systems. This is not something that you do everyday. It’s a very specialised area. This fuel has been pushed from our end to be used at the higher end of the octane rating, and also to have different components in order to get it where we want it to be, which can also mean that it is something that will eventually be used on the road. That may be next year or in two years time.”

Track proven

In other words, there’s always something Shell can glean from Le Mans and other endurance races on the calendar that can filter through to road-going vehicles? “Absolutely,” says Peter. “The track to road thing for Shell is absolutely essential. We wouldn’t be doing this if it didn’t have that technical aspect to it. We need to work with our partners in order to work out how best to develop our products. There’s no top end to where we go with it next. We just need to find out the next step, such as what other components can we put in to reach the best performance in terms of reliability, economics, efficiency, all of these factors.”

The technician

Marcel Ehlert, Shell Motorsport Fuel Scientist, spends much of his time inside the mobile fuel lab at races. When he’s not there he’s catching up on some sleep in a camper van that he shares with other colleagues. He sounds equally passionate about the job in hand. “All the cars are running on a special blend of Shell V-Power,” Marcel says, standing alongside a row of high-tech testing equipment. “So it’s got the same name as the forecourt counterpart, but it’s a different blend of fuel. It’s specially designed for racing, but there are still many things in it that are the same as the forecourt version.”

Guarded secret

Though as you’d expect, Marcel isn’t about to give too much away about the breakdown of the fuel. “The components are the same, but the mixture is different,” he says of the link with conventional fuel. “Initially it has to be created and made sure that it passes all of the checks, then smaller 50 litre drums are passed on to the teams, who test it on their engines. We’ll send it to three to five teams at the same time. The relationship with the teams is a huge part of the whole thing, and it’s the same for the oil side of things too.”

Long term

“The fuel has been designed for the whole season, so that includes the six other races throughout the year,” furthers the fuel tech. “That means we have to create this huge batch of fuel at the start of the year and from that main tank we take whatever we need for the events. The ACO orders the fuel and we bring it in by tanker or drums, depending on where it is. So we brought 270,000 litres here, did a first fuel delivery at the end of May to fill up all of the 60 underground tanks, they hold about 3,000 litres each if you fill them up completely. Then, after the testing and qualifying sessions, we filled them up again on the day before the race.”

Right amount

This is a delicate balancing act in order to ensure that the fuel is not only up to standard, but that there is also going to be enough available. “We will only know after the race just how much is left over, but all of the fuel that is left inside the tanks will get pumped back out again. When it’s back in Hamburg we have to carry out more checks and, if it’s still okay, then it will be reused,” Marcel adds.

Transport time

The racing fuel makes its way around the globe by sea, due to the cost savings involved in moving a heavy, sloshing cargo from A to B. “There’s a whole plan worked out for the season,” Marcel explains. “Which includes preferred shipping dates, but there is also a contingency in place for anything that might go wrong. The company that does the shipping for us has a tank that holds 70,000 litres and will then do a drumming run, which will usually be about 100 to 140 drums in one go. In that respect, we always check the first and last drum, which is something we learned in Formula 1.”

Cleaning regime

It is vital during the whole process that fuel lines and associated kit, including the storage tanks, are kept spotlessly clean. Equipment gets flushed out to ensure there’s no contamination, usually with solvent; any traces of which evaporates before the next batch of fuel is shipped in. “The worst case scenario would be for the fuel to be contaminated with something from your system,” Marcel states. “But, it’s even worse if you don’t really know where. The easiest thing is when you spot a different component in the mix during testing that is obviously coming from something like a cleaning solvent.”

The test bed

One of the main devices the truck has is the gas chromatograph, which is connected to a screen that displays vital data. This comes via a screen featuring two lines; one blue and one red. Blue is the reference sample, while the red one is a sample taken from a car. It’s from this that the technicians are always looking out for any irregularities. “We use a similar service in Formula 1 for the Ferrari team, so the analytical process is much the same,” explains Marcel.

Atomised components

“These machines atomise the fuel in very, very tiny amounts. We have these small 2 millilitre samples, but only 0.1 millilitres gets taken into the system and is vaporised. Flame ionization detectors help the team scrutinize these ‘fingerprints’, which in turn means that quality is controlled and the Shell team hopefully don’t get any unwanted surprises along the way.

The drivers’ perspective

Elsewhere in the bustling paddock area, James Calado, one of Ferrari’s AF Corse drivers, is enjoying his fourth race at Le Mans. “Any driver at Le Mans is lucky to be here because it’s a prestigious race, one of the best in the world,” he says. “The atmosphere is extraordinary with all the fans and everything. Obviously we train a lot, as much as we can. I personally enjoy cycling and can get through hundreds of miles in a week. For Le Mans we just need to make sure that we retain a bit more energy. After the race I’m destroyed, but mentally much more than physically. It’s just so difficult to sleep because you’ve got huge amounts of adrenalin, so it’s really tough trying to settle down.”

Saving grace

The marathon race has its good points however… “Le Mans isn’t so bad because you’ve got the straights, which give you a little bit of a breather. Whereas places like Sebring and Daytona, you’re always going around a corner, so that’s really tough.” Meanwhile, Belgian racer Jean-Paul Libert, himself a veteran of the Le Mans race during the 90s, is amazed at how the technical capabilities have changed for the better over the years. “Today, there are still over fifty cars in the race,” he says. “Which in the old days was unheard of.”

And, it seems, part of that is down to the almost obsessive enthusiasm for quality fuel that comes from the technicians hiding inside the Shell mobile laboratory.

Rob Clymo has been a tech journalist for more years than he can actually remember, having started out in the wacky world of print magazines before discovering the power of the internet. Since he's been all-digital, he has run the Innovation channel for a few years at Microsoft, as well as turning out regular news, reviews, features and other content for the likes of Stuff, TechRadar, TechRadar Pro, Tom's Guide, Fit&Well, Gizmodo, Shortlist, Automotive Interiors World, Automotive Testing Technology International, Future of Transportation and Electric & Hybrid Vehicle Technology International. In the rare moments he's not working, he's usually out and about on one of the numerous e-bikes in his collection.