EVs are turning into video games, and it's really not a good thing

I’m concerned about car maker’s newfound reliance on over-the-air software updates

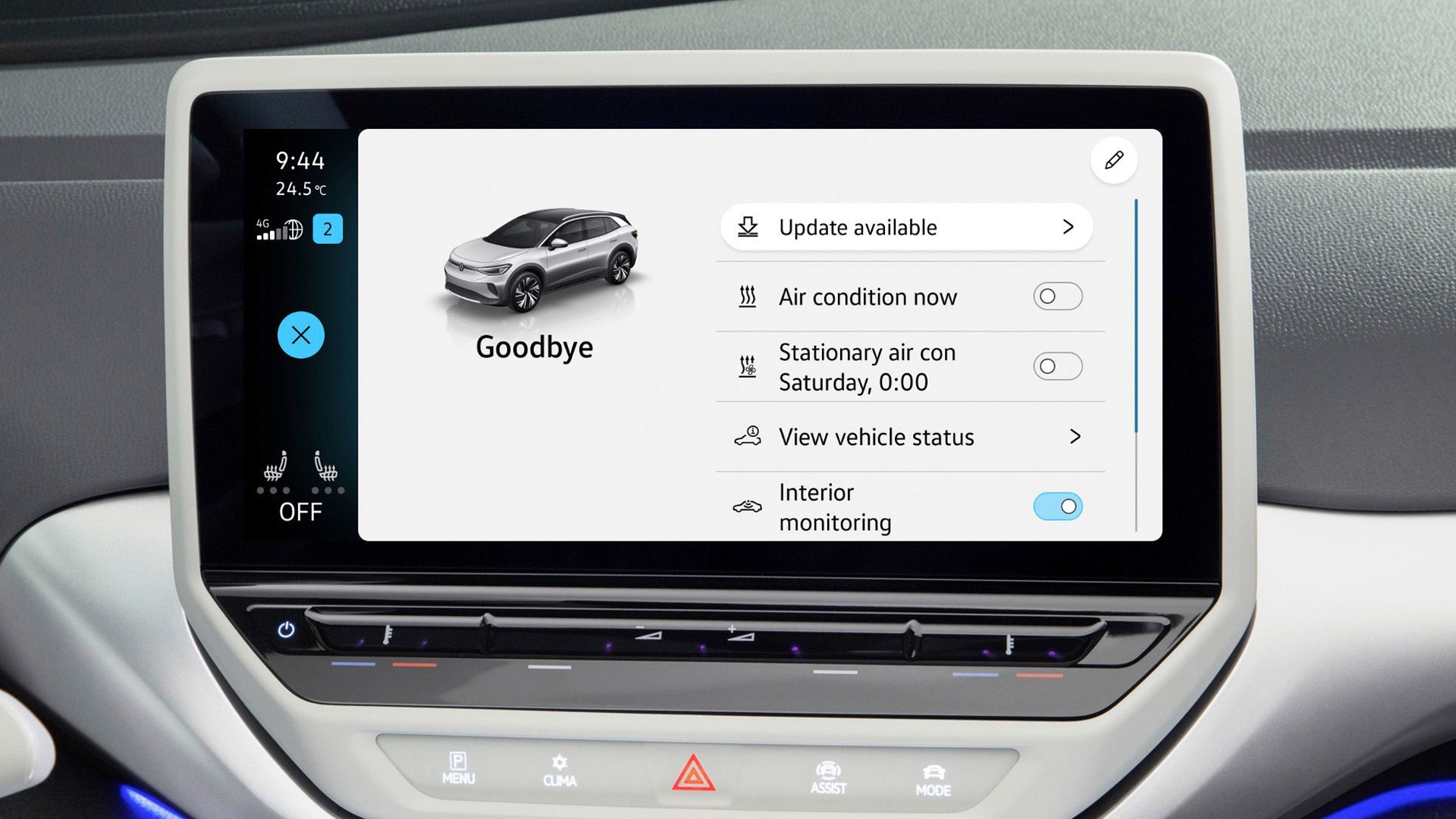

Over-the-air (OTA) software updates seem like a great idea for electric cars. Just look at how much the infotainment system of an early Tesla Model S changed over the years, with the interface becoming slicker and even gaining new features as the cars got older. OTA updates also save the driver time, as problems can be fixed remotely instead of arranging a visit to the dealership.

But I’m concerned that carmakers are in danger of becoming overly reliant on fixing things after the car has shipped.

I’ve been thinking about this for a while, but what really highlighted the issue for me was the recent Volvo EX30 launch drive. Although a great car that I can’t wait to spend more time with, it simply wasn’t finished when journalists were invited to review it. I’m not talking about the way it drives; the acceleration is rapid, the steering is sharp and the ride is good. It promises to be a fantastic compact EV for young families, with good range, smart styling and an attractive price.

But the software was a problem. Interface elements would occasionally obscure one another; the mirrors were slow to respond to adjustments made via buttons on the steering wheel; the glovebox on the second car I drove – operated by a tap of the touchscreen – refused to open. Not ideal if a driver needed to present their licence, insurance certificate or other such documents often kept in there.

It was only when I raised these issues that Volvo conceded the cars were pre-production, and that the faults I encountered would be looked at before customer cars arrive in 2024. And it wasn’t just the obvious failures like the glovebox that Volvo would address. A representative said the company would look into all manner of interface elements I felt could be improved, such as how a large, ugly graphic completely blocks the navigation map when the parking sensors are triggered. He said our half-hour chat felt like a consultation session. I regret not sending him an invoice.

Extrapolate this just a little and we could soon end up in a similar situation to the video game industry, where gamers are often frustrated by enormous day-one patches that need downloading and installing before the game can be played. I appreciate the biggest patches are created because the game doesn’t fit on a single disc and a software download is probably cheaper and simpler than producing a second disc. But it has become the norm to encounter a sizeable patch made to fix things the developers didn’t have time to commit to disc.

Car manufacturers can certainly benefit from this. Given the lead time between a vehicle leaving the factory and arriving with the buyer can be measured in weeks, this presents a nice window of opportunity for last-minute fixes and tweaks, all ready to download and install the moment the car is switched on and connects to 4G or the owner’s Wi-Fi network. But, as sure as day follows night, the convenience of OTA updates will be followed by laziness. “Ship now, patch late,” an automotive UI designer has undoubtedly already said.

Get all the latest news, reviews, deals and buying guides on gorgeous tech, home and active products from the T3 experts

Manufacturers are also now wrestling with how a car downloads and instals a major firmware update, yet retains the ability to be driven at any moment. Not using your phone for 10 minutes while an update instals is one thing, but jumping in your car in an emergency, only to find it installing new firmware and thus undriveable, is quite another.

And what if the OTA update goes wrong? It used to be common sense to wait a few days after Apple released a major iPhone software update, just in case something was amiss and handsets were bricked.

Predictably, we’re starting to see this happen with cars. Only this week, Rivian blamed “a fat finger” on the wrong software update being sent out to customer cars. The faulty software impacted the infotainment system of both its R1T electric truck and R1S SUV, with the usual remedies of a reset or sleep cycle not working. Rivian says affected customers will be contacted, and that a remedy “may require physical repair in some cases,” suggesting the rogue patch might have caused significant damage. “This is on us - we messed up,” the company added.

Cars with a limited shelf life

The next parallel between electric cars and consumer technology is how products dependent on software updates have a fairly limited shelf life. Unlike an older car that can theoretically live for as long as there’s fuel to put in its tank, it seems unlikely that manufacturers will issue patches and software updates decades after an EV is built. Administer another gentle dose of extrapolation and I fear that trying to run today’s EVs in 2050 will be akin to booting up a 2007 iPhone today. It’ll turn on and connect to your Wi-Fi network. You might even find an old-style SIM card for it, but even apps as simple and ubiquitous as WhatsApp can no longer be installed.

Will the £100,000 EV you buy today eventually become obsolete? If cars are to follow the path of consumer tech like phones, we can predict with reasonable accuracy that as they age they’ll stop receiving the latest flagship software features. Next, they’ll only be granted access to crucial patches and bug fixes, before eventually being branded obsolete, their operating system frozen in time with no way of being updated to keep pace with an ever-changing world.

Might an old EV, decades down the line, no longer communicate with the latest public chargers? That could be a stretch, but I can see EVs losing features like using a smartphone as a key, as phones and encryption technologies evolve beyond what the car’s hardware was originally intended for. Manufacturers bake in a degree of headroom here, with car processors overspecified today in the hope that they’ll be able to deal with more power-intensive software tomorrow. But anyone who has ever bought a computer knows that headroom doesn’t last forever.

Extrapolate again (sorry) and the logical conclusion to all this is a future where cars are treated exactly like phones, games consoles and computers are today. They are designed, developed, built and updated, until one day they aren’t. They are then patched for a while longer, before being deemed obsolete and, whisper it, recycled.

I had a conversation with Frank Weber, BMW’s chief technical officer of development, about this earlier in 2023 and that chronology – build, update, patch, make obsolete, recycle – is broadly what the company expects of its cars from now on. I suspect all manufacturers have a similar plan, save for those building cars deemed collectible and therefore with inherent future value. Ferrari, Bentley, Rolls-Royce; that sort of thing. The rest assemble cars today that already have a plan for how they’ll be dismantled and recycled tomorrow.

Unless manufacturers can somehow guarantee that, when vehicles are made obsolete, they receive a final software version that is absolutely bombproof, with no chance of ever going wrong, there will be no more classic cars. At least ones that can actually be driven. I joked to Weber that as cars become consumer electronics with a defined shelf life, there will be nothing to add to BMW’s heritage collection. A year on, and I now realise that isn’t far from the truth.

Alistair is a freelance automotive and technology journalist. He has bylines on esteemed sites such as the BBC, Forbes, TechRadar, and of best of all, T3, where he covers topics ranging from classic cars and men's lifestyle, to smart home technology, phones, electric cars, autonomy, Swiss watches, and much more besides. He is an experienced journalist, writing news, features, interviews and product reviews. If that didn't make him busy enough, he is also the co-host of the AutoChat podcast.